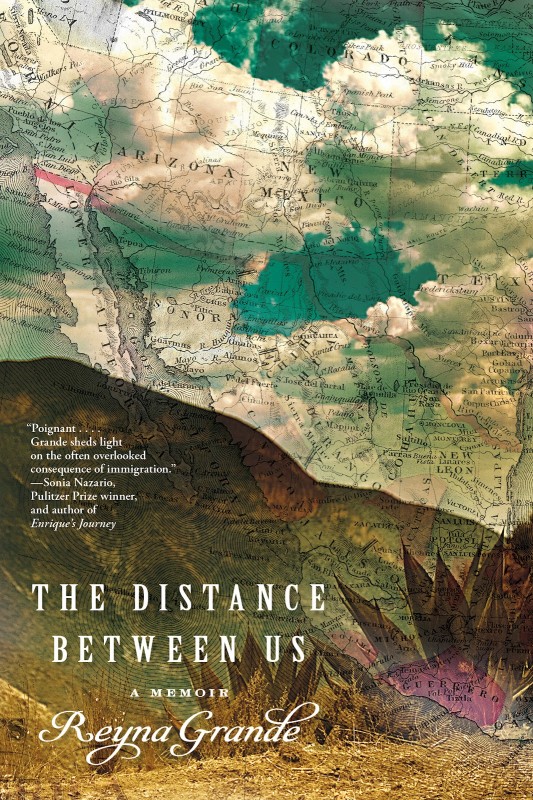

08 Oct / The Distance Between Us: A Memoir by Reyna Grande

She was left at age 2 by her father, then at 4 watched her mother go; both parents braved the border into “El Otro Lado” (The Other Side) to make enough American dollars to reunite the family in their dream house someday. The youngest of three children, Reyna Grande grew up with extended relatives in Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero in southern Mexico, under the iron control of her paternal grandmother – who certainly lives up to her given name, Evila: “‘I can be sure my daughters’ children are really my grandchildren,'” she often told Reyna, Carlos, and Mago, as if to excuse the unfair abuse she directed at her son’s young offspring.

She was left at age 2 by her father, then at 4 watched her mother go; both parents braved the border into “El Otro Lado” (The Other Side) to make enough American dollars to reunite the family in their dream house someday. The youngest of three children, Reyna Grande grew up with extended relatives in Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero in southern Mexico, under the iron control of her paternal grandmother – who certainly lives up to her given name, Evila: “‘I can be sure my daughters’ children are really my grandchildren,'” she often told Reyna, Carlos, and Mago, as if to excuse the unfair abuse she directed at her son’s young offspring.

The parents’ reunion on ‘the other side’ produces an American sister, making the three left-behind siblings fearful that they’ve been replaced. But then Mami returns with only Betty, just over a year old; elusive Papi chooses to remain in the U.S. with his new wife. Mami is forever changed, and she’s never quite able to repair the strained relationship with her children.

Just before Reyna turns 10, “the Man Behind the Glass” – the only way she remembers her absent father – reappears in Abuelita Evila’s house to reclaim his four children. Mami will not let Betty go out of spite. Reyna, too, almost gets left behind, initially deemed too young to attempt the border crossing. The third try proves successful and suddenly the three siblings are beginning new lives on the other side with a stranger-father and a less-than-welcoming stepmother. Cultural, social, educational adjustments are expectedly challenging, but nothing is as difficult as learning to live with their mercurial, alcoholic, violent father. That titular ‘distance’ – between countries, homes, most of all, within families – remains a haunting, constant presence throughout the pages.

Had The Distance Between Us not been a summer high school English requirement for our son, I admit I wouldn’t have read it. That Grande was then writer-in-residence briefly this fall, which included an all-community public program, provided further inducement. The student-planned-and-performed introduction to her presentation was especially moving: almost a dozen girls from the school’s Latina affinity club shared intimate, stirring reactions about how much Distance meant to each. “I didn’t know my story could be a book like this” to “I didn’t know a Latina could be a famous writer.” The significance of discovering Distance at such a pivotal point in their young lives was obvious, and heartfelt. Critics, too, have been mostly laudatory: Distance was a finalist for the 2012 National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography.

And yet … in spite of the sincere appreciation for the story, the survival, the achievement contained within Distance, as literature, the memoir falls short. Although sometimes referred to as the Mexican Angela’s Ashes (the Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir by Frank McCourt about growing up in abject poverty in Brooklyn and Ireland), Distance lacks the literary prowess that makes Ashes lyrical in spite of the brutality, mellifluous in spite of the suffering. Grande’s few poetic moments – the forever connection between mother and daughter via umbilical cord; the beauty she recognizes amidst the deprivation of her home village because she knows no other way of life – are not enough to make the text anything more than descriptive, even pedestrian, and ultimately disappointing.

For the high school Latinas for which Distance was such an empowering read, might I suggest building on that momentum: Luis Alberto Urrea’s Border Trilogy, any Sandra Cisneros title, U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s My Beloved World, are just a few alternative titles that come immediately to mind. That said, to read Distance is to bear witness. With immigration such the au courant hot-button topic, Distance is inarguably an accessible introduction from which to explore further.

Readers: Young Adult, Adult

Published: 2012