Representation in Children’s Literature

On this page, you will find information about representation and diversity in children’s literature, meet two experts who study literature, and access links to helpful resources about diverse books.

This page was created for the 2019 Asian American Literature Festival, a biannual event held in Washington, DC that brings Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) writers, poets and professors of literature together to celebrate and discuss AAPI literature. The theme for the 2019 festival was Care + Caregiving, and this page was created to focus on children’s literature, and how selecting diverse books for the classroom can be a form of care for students. To learn more on the topic of representation in children’s literature and the lack thereof, Sarah Park Dahlen, Association Professor of Library and Information Science at St. Catherine University, and Noreen Naseem Rodriguez, Assistant Professor of Elementary Social Studies at Iowa State University, were interviewed.

This page includes:

• Q&A with Sarah Park Dahlen and Noreen Naseem Rodriguez

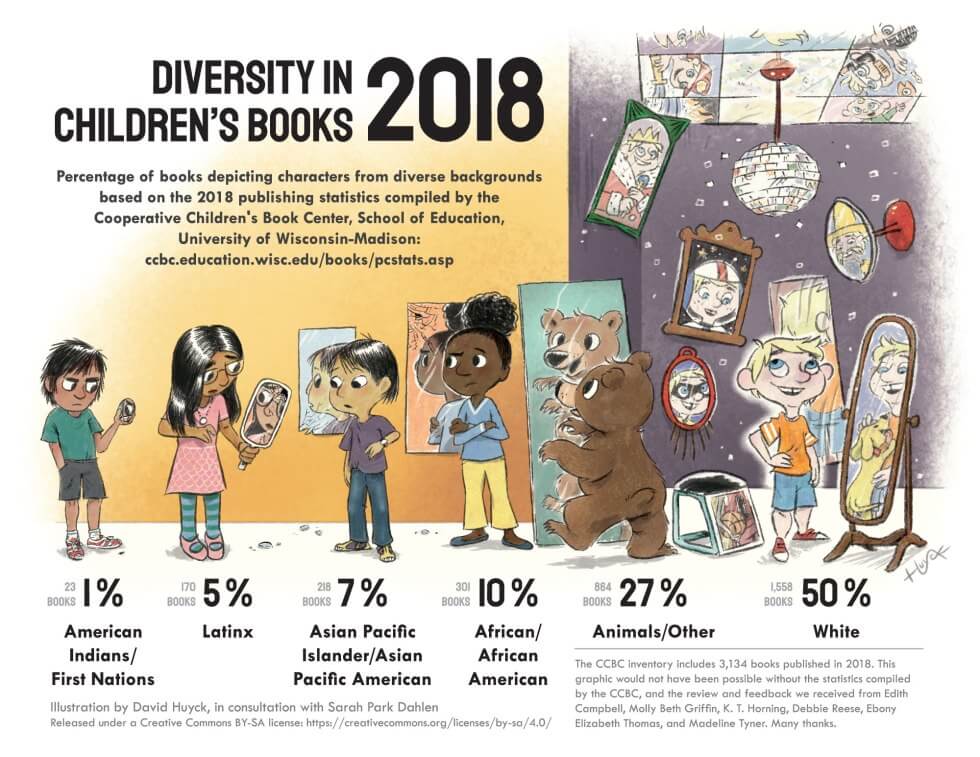

• Infographic on Diversity in Children’s Books for 2018

• Links to studies about representation in children’s literature

• Links to book recommendations for varying age and grade levels

To explore these resources and learn more about this topic, keep scrolling down this page.

Let’s meet Sarah Park Dahlen, Associate Professor of Library and Information Science at St. Catherine University, who shared her thoughts on the 2019 Asian American Literature Festival Theme, children’s literature as literature, and the importance of including Asian Pacific American voices in literature and libraries.

How does the Festival’s theme of Care + Caregiving resonate in your research about youth literature and library services?

The Festival's theme of Care + Caregiving resonates strongly with me in terms of the work we are doing in children's literature and library services. One of the main reasons why we advocate for diverse and accurate representations of Black and Indigenous Persons of Color (BIPOC) in youth literature is because we care so deeply about our young people and their families. Many of us creating or studying youth literature grew up either invisible or seeing mostly distorted and inaccurate images of ourselves in the media around us, and we don't want today's young people to have the same experiences. Every child deserves to see themselves in the media around them. Every child needs to see many different children in the media around them. In doing this work for young people, we are caregiving.

My colleagues and I are also committed to helping create a robust body of scholarship on Asian American children's literature, and this includes being in conversation with children's book creators such as those speaking at the Asian American Literature Festival. Together, we are a community with the shared goals of creating and providing access to good books for all children. Supporting one another's work and mentoring up and coming book creators and scholars are another form of caregiving.

During the Festival, you will be speaking on a panel about children’s literature. Why do you think it is important to have these conversations at this time?

Some people don't think children's and Young Adult (YA) literature is literature, but it is; it's literature written for a younger audience. Youth literature is important because it has such a strong socializing impact on young readers. Our absence speaks volumes. Our presence - whether accurate or distorted - sends strong messages as well. For example, if the majority of children's books depicting Asian people are immigration stories, they are depicting only one and a limited aspect of our experiences. If the majority of stories featuring Japanese Americans take place during the incarceration, that is an important but limited view of Japanese Americans. We need many, many books featuring Japanese Americans in a variety of settings and time periods so we can have a broad understanding of their diverse experiences. If we never see ourselves reflected in fantasy, that says something about the "imagination gap" that Dr. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas so eloquently describes in her book, The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games (2019).

It has always been important to have these conversations, but it is especially important to have them today, at a time when we're having such fraught conversations about race and racism at the national level. There's a lot of misinformation and silence out there regarding Asian Americans (for example, we are less visible in deportation debates), and elevating our narratives in a variety of spaces can combat that. To be clear: it's not that Asian Americans aren't advocating or speaking up - we have long been artists and writers and activists in many different spaces - but we need to continue doing this work and building stronger communities across multiple intersections of identities with the shared goals of equity and justice.

It has always been important to have these conversations, but it is especially important to have them today, at a time when we're having such fraught conversations about race and racism at the national level. There's a lot of misinformation and silence out there regarding Asian Americans (for example, we are less visible in deportation debates), and elevating our narratives in a variety of spaces can combat that. To be clear: it's not that Asian Americans aren't advocating or speaking up - we have long been artists and writers and activists in many different spaces - but we need to continue doing this work and building stronger communities across multiple intersections of identities with the shared goals of equity and justice.

What does it mean for you to have Asian Pacific American voices and narratives represented in children's libraries?

A few years ago, I published an essay that began, "I didn't know I was invisible until college." Though I read voraciously as a child, I never saw Korean people in my books. I didn't know Korean Americans could be in literature until I was in college (Helie Lee's Still Life With Rice was one of the first Korean American-authored books I read), and I didn't know we could be in children's literature until I was in graduate school. An Na's A Step from Heaven was the first young adult novel I read that reflected so much of my own personal story. I went to library school because I didn't want children - both Asian and non-Asian - to have the limited reading experiences I had had as a child.

For a non-Asian reader, children's literature may be one of the few times they encounter Asians and Asian Americans. For an Asian American reader, seeing ourselves and our experiences reflected in the books we read may be affirming. This idea - that literature serves as windows and mirrors - was put forth by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop in her famous 1990 article, "Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors." For too long, many of the stories about Asians and Asian Americans were created by people without the lived experiences of being Asian. Today, we have many more stories about the Asian diaspora, but these counter narratives have to do the heavy work of unmaking and remaking our images in the popular imagination.

I keep returning to what Viet Thanh Nguyen posted on Facebook and Twitter when the film Crazy Rich Asians came out: "Basically, the majority has an economy of narrative plenitude. All the stories are about them. A bad story is just a bad story, no big deal, since there's so many stories already. Narrative plenitude means that you have the possibility of excellence, while mediocrity is perfectly acceptable... The minority has an economy of narrative scarcity. Almost none of the stories are about them. A bad story (or negative stereotype) is horrifying, demeaning, demoralizing. A good story is everything. Mediocrity is read as the failure of the minority, not just the individual" (Viet Nguyen, Facebook post, August 16, 2018). He continued, "We want narrative plenitude, but we can only achieve it when we have control or influence over the economy of narrative. Individual writers or artists can't achieve narrative plenitude. It takes a movement to struggle at all levels of economic and narrative production, as well as politics."

This is true for children's literature: we are an essential component of this movement for narrative plenitude, and we need to be in control of creating our own images. Asian American children's book creators and scholars are in many different spaces (educator conferences, library conferences, etc.), and being at the Festival is another way to ensure we are part of the conversation and revolution in terms of Asian American cultural production.

This is true for children's literature: we are an essential component of this movement for narrative plenitude, and we need to be in control of creating our own images. Asian American children's book creators and scholars are in many different spaces (educator conferences, library conferences, etc.), and being at the Festival is another way to ensure we are part of the conversation and revolution in terms of Asian American cultural production.

Illustration by David Huyck, in consultation with Sarah Park Dahlen

Let’s meet Noreen Naseem Rodriguez, Assistant Professor of Elementary Social Studies at Iowa State University, who shared her thoughts on the importance of representation in children’s literature and in the classroom.

Why is it important for young students of color to see themselves represented in books they are using in the classroom, such as social studies textbooks, novels, and picture books?

Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop (1990) argued that “Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation and readers often seek their mirrors in books." Dr. Bishop also said, “When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part.”

I think this idea of searching for mirrors is so important, and is also true in terms of the history we learn. I never learned about Asian Americans immigrating to the United States in the 1970s in school - I knew this was something my parents and their friends did, but it was never acknowledged in school. Honestly, we never learned about immigration after Ellis Island. When we think about the historical figures and changemakers who are taught in school, those examples are generally limited to landed, white, cisgender, heterosexual, abled Christian European men. People of color, women, and people with historically marginalized identities are rarely a part of the U.S. historical narrative, which gives the mistaken impression that we didn't contribute to the making of these United States, which is far from the truth. But this exclusionary narrative is pervasive, and can be found everywhere, from textbooks to trade books to pop culture. For those who are marginalized in society, whether due to their race, ethnicity, language, culture, religion, ability, gender, sexuality, immigration status, class, or family makeup, or these and other aspects of identity, it is far easier to find (hi)stories that don’t reflect their experiences than ones that do in ways that are meaningful, authentic, and avoid stereotypes.

What do you want teachers to be mindful of as they consider titles to include in their curriculum for the coming school year, and beyond?

I think it's important for teachers to actively seek out books that are both mirrors of their students' experiences as well as windows into the experiences of others. But as teachers find more "diverse" books that go beyond normative experiences and stories, I urge them to consider three things:

First, assess the authenticity of the text. On Twitter, the hashtag #OwnVoices reminds us to consider the importance of authorship when it comes to telling stories that are authentic and avoid stereotyping and misconceptions.

Second, consider how they are including these books within the broader curriculum. Do they repeat or connect to ideas mentioned elsewhere? If teachers know they need to include more stories about disability, are they clustering them all in a single week during the school year or are they really trying to find examples that connect to a range of topics all year long? Are all the books about disabilities featuring the same kinds of family structures, identities, and experiences? Be intentional about diversity within topics as well and try to avoid what Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche describes as "the danger of a single story" - which is an incomplete narrative that ultimate perpetuates stereotypes rather than dismantling them. The Children's Literature Assembly has a very helpful document designed to guide teachers towards critically analyzing and using diverse texts in the classroom.

"Children from dominant social groups have always found their mirrors in books, but they, too, have suffered from the lack of availability of books about others. They need the books as windows onto reality, not just on imaginary worlds. They need books that will help them understand the multicultural nature of the world they live in, and their place as a member of just one group, as well as their connections to all other humans. In this country, where racism is still one of the major unresolved social problems, books may be one of the few places where children who are socially isolated and insulated from the larger world may meet people unlike themselves. If they only see reflections of themselves, they will grow up with an exaggerated sense of their own importance and value in the world - a dangerous ethnocentrism.”

-Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop

Third, how can these books complicate existing narratives in history books and popular culture? For example, many books about the civil rights movement have happy endings that depict the resolution of racial injustice. We know that injustice remains in our society in many forms, and often students bear direct witness to this and have unanswered questions. Don't be afraid to have these conversations with children and youth! They are eager to discuss current events and ongoing issues related to power and injustice, and it's usually the adults who feel uncomfortable and unwilling to talk. We need to have the courage to create space for these conversations and to reveal ourselves as not having all the answers, but being willing to learn more and do better.

What does it mean for you to have Asian Pacific American voices and narratives represented in K12 classrooms?

I have always searched for stories similar to mine in the books I read. For me, this was especially difficult to encounter because I'm intraracially mixed - my father is from Pakistan and my mother is Filipina. But I was never assigned a book by a Filipino author until my Master's program, when I was in my late twenties. I remember bursting into tears when I saw lolo, the Tagalog word for grandfather, in print. Until that moment, I had no idea how badly I had wanted that kind of affirmation. And now that I have children of my own, I'm especially passionate about finding books for children to connect with in similar ways, as early as possible.

What does it mean for you to have Asian Pacific American voices and narratives represented in K12 classrooms?

I have always searched for stories similar to mine in the books I read. For me, this was especially difficult to encounter because I'm intraracially mixed - my father is from Pakistan and my mother is Filipina. But I was never assigned a book by a Filipino author until my Master's program, when I was in my late twenties. I remember bursting into tears when I saw lolo, the Tagalog word for grandfather, in print. Until that moment, I had no idea how badly I had wanted that kind of affirmation. And now that I have children of my own, I'm especially passionate about finding books for children to connect with in similar ways, as early as possible.

A couple examples I'd like to share are Jasmine Toguchi, Mochi Queen by Debbie Michiko Florence and The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson. My youngest daughter is super spunky, like Florence's character of Jasmine, and also like Jasmine, she loves mochi. The first time I saw that book, I was stunned by the resemblance between my daughter and Jasmine's character, and she saw it too when I shared it with her. In The Day You Begin, Woodson depicts young children who are starting in a new school. While the anxiety around making friends and being in new places is relatively universal, I love that Woodson centers a range of characters. In particular, one character brings "ethnic" food for lunch and deals with the disgust of a peer; this is an experience that I, and many Asian Americans I know, have dealt with personally in school. I think it's important that APA students have multiple opportunities to see themselves reflected in the classroom in ways that touch on a range of their identities, and these two book examples are ways that teachers can easily bring some of those stories into the classroom. Of course, teachers should also consider who is in their school and larger community and draw inspiration from their students in terms of what stories they might need to include.

Lastly, as an educational researcher, I want PK-12 teachers to know that Asian Pacific Americans are the least represented racial group in U.S. history curriculum. At best, the Chinese in the 1800s and Japanese American incarceration are included, but rarely are other groups covered, particularly in the last century. Immigration is still often relegated to Ellis Island, and with younger students, Asian American holidays and foods may be included seasonally through arts and crafts, but these topics are generally taught in ways that emphasize their foreignness and difference from "traditional American culture" and may be inaccurate and stereotypical. Even worse, Pacific Americans are almost never taught. There's a lot of work to be done to change the troubling ways that Asian Pacific Americans are included, or not included, in classrooms and we need educators to do this work throughout PK-12. APAs are a part of U.S. history and with the wealth of resources we have available now, we need to fully acknowledge that in schools.

Watch: Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, “Mirrors, Windows & Sliding Glass Doors”

Watch: Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The Danger of a Single Story”

Read: Children’s Literature Assembly Position Statement on the Importance of Critical Selection and Teaching of Diverse Children’s Literature

Website: Q&A with Ebony Elizabeth Thomas on the importance of diverse books

Lastly, as an educational researcher, I want PK-12 teachers to know that Asian Pacific Americans are the least represented racial group in U.S. history curriculum. At best, the Chinese in the 1800s and Japanese American incarceration are included, but rarely are other groups covered, particularly in the last century. Immigration is still often relegated to Ellis Island, and with younger students, Asian American holidays and foods may be included seasonally through arts and crafts, but these topics are generally taught in ways that emphasize their foreignness and difference from "traditional American culture" and may be inaccurate and stereotypical. Even worse, Pacific Americans are almost never taught. There's a lot of work to be done to change the troubling ways that Asian Pacific Americans are included, or not included, in classrooms and we need educators to do this work throughout PK-12. APAs are a part of U.S. history and with the wealth of resources we have available now, we need to fully acknowledge that in schools.