17 Dec / Yokohama Yankee: My Family’s Five Generations as Outsiders in Japan by Leslie Helm

‘Sprawling’ barely begins to describe journalist/editor Leslie Helm‘s ambitious family history that spans nearly a century-and-a-half, three continents, and the titular five generations of a German Japanese American family with current branches spread throughout the rest of the world. Prompted by the death of his difficult father in 1991, and further spurred by the imminent adoption of two children soon thereafter, Leslie embarks on a personal quest to discover the complicated layers of his mixed-race heritage.

‘Sprawling’ barely begins to describe journalist/editor Leslie Helm‘s ambitious family history that spans nearly a century-and-a-half, three continents, and the titular five generations of a German Japanese American family with current branches spread throughout the rest of the world. Prompted by the death of his difficult father in 1991, and further spurred by the imminent adoption of two children soon thereafter, Leslie embarks on a personal quest to discover the complicated layers of his mixed-race heritage.

In 1868, Julius Helm, then 28, left his father’s 400-acre farm in Rosow, Germany, for a new American life only to find his options were limited to being a common laborer in Minnesota. One year later, the transcontinental railroad took him to San Francisco, where he narrowly missed his intended ship to China and landed instead in Yokohama in 1869.

Barely a decade earlier, Japan had been opened to foreign trade, and Yokohama was a primary entry point into the still-insular country. Julius’ arrival was fortuitously-timed: after moving from various minor jobs and apprenticeships, working for the German consul, and training Japanese soldiers, Julius eventually established himself – and his future generations – as an important merchant presence in Yokohama. Five of his nine siblings followed him to Japan. And his Japanese wife and their four hapa children insured the Helm family’s lasting Japanese ties.

Japanese ancestors, Japanese spouses, Japanese births left most of the Helm generations conflicted over the next 140 years: ‘The Helm relatives I knew were people caught between cultures,” Leslie observes. “… Most had lived on three continents and spoke four languages, yet they never felt at home in any one country.” Caught between a belief of superiority over the Japanese and too often a shameful insecurity over mixed blood, each generation of Helms battled doubts about their identity. Four generations removed from Julius, Leslie is the first to explore, explicate, and accept his challenging relationship with the country of his birth. Ironically, the fifth and latest Helm generation returns the family (at least Leslie’s branch) to Japanese ethnic ‘purity’ as both Leslie and his older brother adopted Japanese children; the children’s American upbringing, however, guarantees the Helms’ cultural hybridity.

Working with unpublished memoirs and diaries (including Julius’ biography “[r]e-written from his personal notes, by his brother Karl”), aging photographs, letters, articles, public records and registries, interviews, and memories, Leslie admirably attempts to corral an unwieldy cast of characters into a single historical narrative. His presentation is not always smooth: sections lag, skip, overlap (Leslie’s father Don’s life story, interwoven throughout, is often jarring to the story’s flow), while certain repetitions are unrelenting (too many of the Helms’ self-loathing doubts and denials). That said, the pages continue turning and fascinating details keep the narrative moving; the book’s latter chapters about the rediscovery of a distant, elderly Japanese cousin and the newly established bond with extended Japanese relatives of Julius’ Japanese wife’s family are particularly memorable.

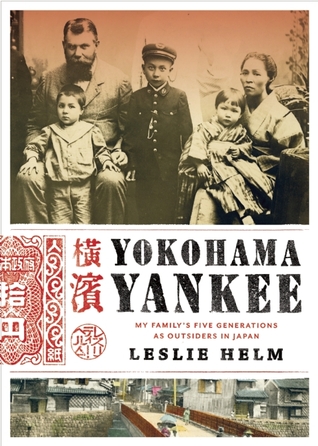

Whatever its narrative pitfalls, this memoir is an undeniable visual success, exquisitely designed with fascinating photographs, historic documents, maps, handwritten notes and passages, travel stamps, and family crests. The mementos add a vibrant intimacy that overshadows any literary missteps. The family that emerges from these pages, with deep roots in Japan yet constantly in flux between wars, migrations and returns, economic opportunities – not to mention languages and cultures – proves to be a resilient force of inspiration, tenacity, and discovery.

Readers: Adult

Published: 2013