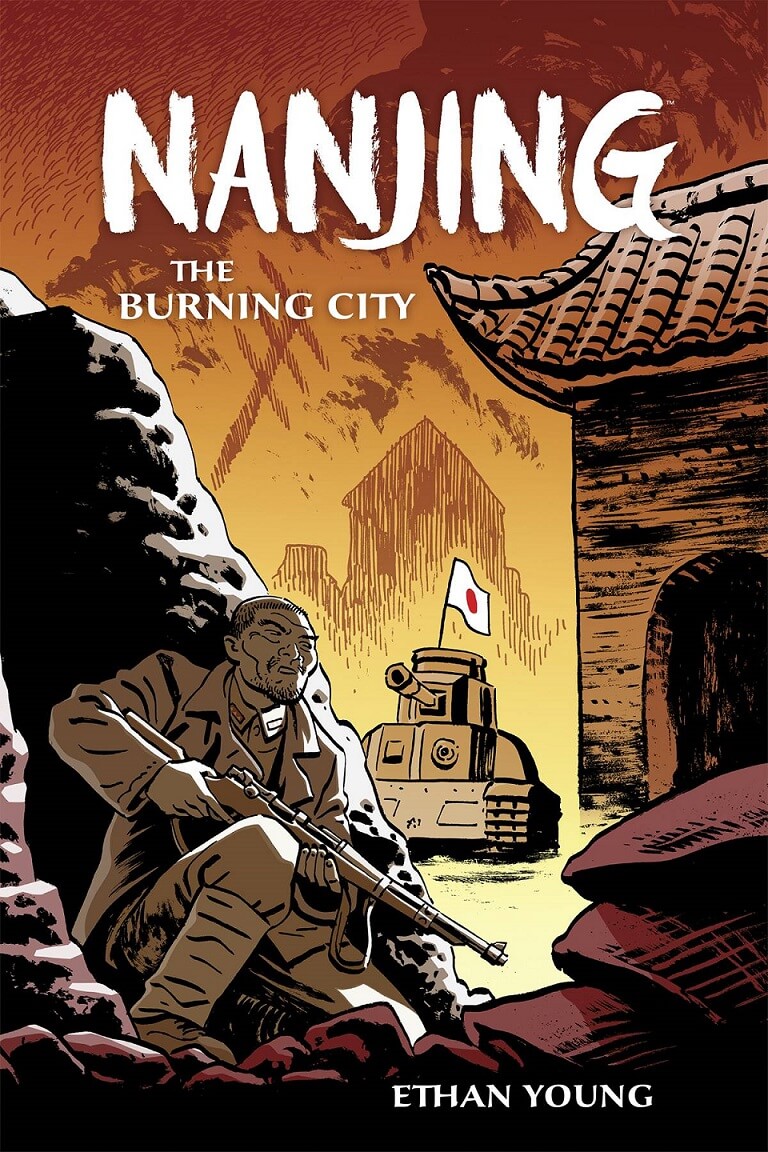

14 Aug / Nanjing: The Burning City by Ethan Young

The late Iris Chang almost single-handedly taught the western world about the horrors of the Nanking Massacre in her 1997 The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. Over six weeks that began with the Imperial Japanese Army’s capture of China’s then-capital city of Nanjing (the current official pinyin phonetic system for Mandarin pronunciation) on December 13, 1937, up to 300,000 Chinese men, women, children were butchered en-masse.

The late Iris Chang almost single-handedly taught the western world about the horrors of the Nanking Massacre in her 1997 The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. Over six weeks that began with the Imperial Japanese Army’s capture of China’s then-capital city of Nanjing (the current official pinyin phonetic system for Mandarin pronunciation) on December 13, 1937, up to 300,000 Chinese men, women, children were butchered en-masse.

Ethan Young, the New York City-born son of Chinese immigrants, debuts what appears to be the first-ever graphic novel about Nanjing. The word ‘graphic’ here certainly takes on new, ironic, anguished meaning.

“The day before the city’s capture,” Young writes in a historical introduction, “high-ranking military officials began fleeing Nanjing in chaos. Many commanders abandoned their own troops without giving any orders for retreat.

“This is a story about the forgotten ones.”

Even as Captain watches one of his soldiers die, he promises another, Lu, “neither one of us are dying tonight.” Lu has no other choice than to trust his determined superior. What they see as they navigate the fallen city is nightmarish beyond words; the inhumane brutality is such that death proves to be the gentler option for civilians caught alive.

“[T]here’s no room for any sentiment during war,” the Captain reminds a Confucius-quoting Lu. But when the pair discovers a family trapped in their home now reduced to rubble, they cannot turn away. As the Japanese descend, the Captain – regardless of personal cost – chooses to hold on to his humanity

Although the politics of war are rarely definable in black and white, in the case of Nanjing, the Chinese – especially the civilians – are clearly the victims of the Japanese Army who are indisputably wrong, evil, who will later be found guilty of mass rape, torture, and executions. And yet Young breathes good and bad onto both sides, showing flawed humanity over and over again: the Captain must make heartless choices, the Japanese soldier whom Lu bludgeons was most likely one of the last ‘good guys’ regardless of his uniform, the Japanese Colonel insists his soldier return the rice they steal from a young Chinese boy and makes it clear he will not tolerate petty theft from his men again.

Young’s is just one chapter in an overwhelmingly grievous episode of the 20th century. The specifics might be fictional amidst a historical backdrop, but in creating names, depicting individual faces both living and dead, Young conjures a haunting microcosm amidst a horrifying event of epic proportions. We can never be ready for this harrowing close-up, but through transformative storytelling, Young rightfully demands we remember “the forgotten ones,” that we bear witness, we learn, and we must ensure such carnage never happens again.

Readers: Young Adult, Adult

Published: 2015