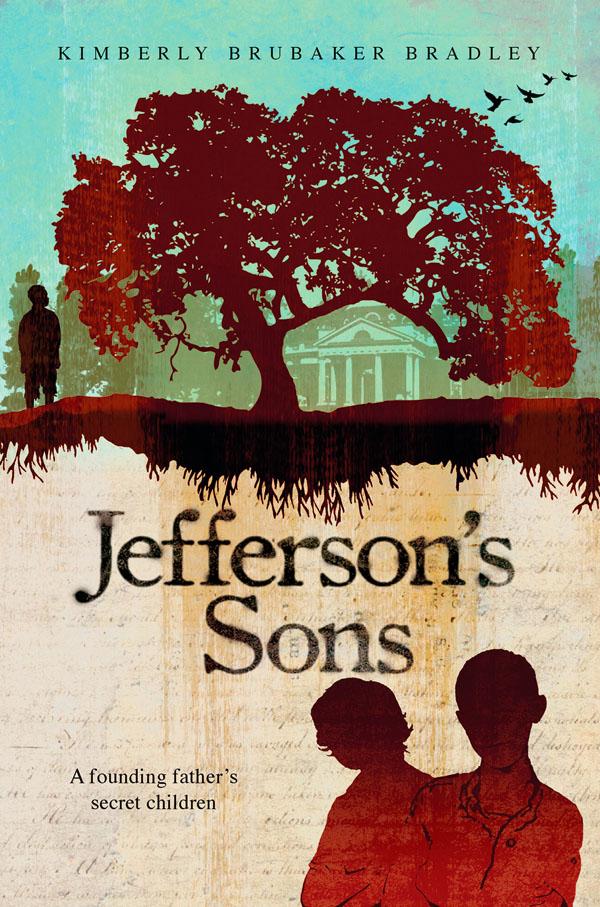

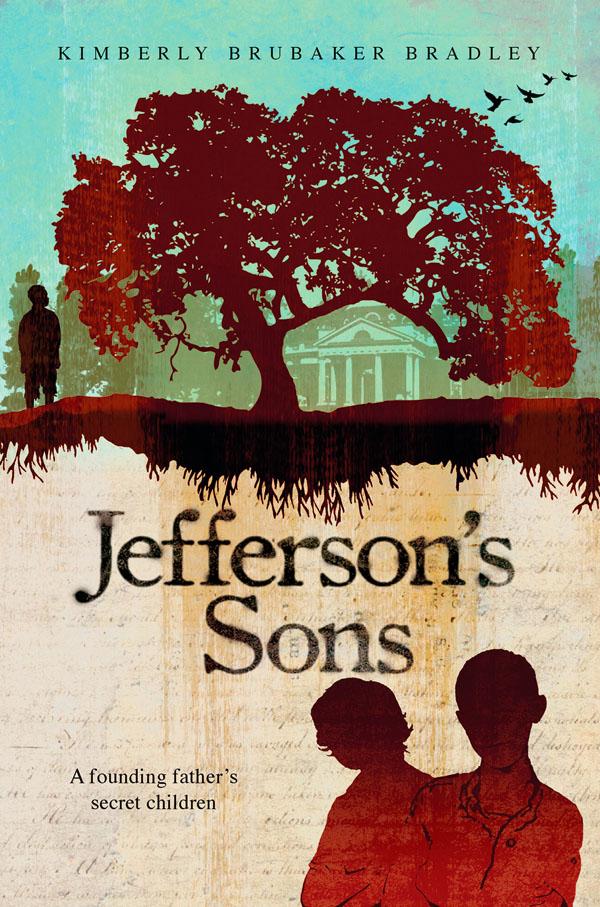

29 Jan / Jefferson’s Sons: A Founding Father’s Secret Children by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley

Let me start with what has been deemed as historical record. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation – which not only owns and operates Jefferson’s legendary home, Monticello, but maintains the most comprehensive website focused on “Monticello, Jefferson, his family, and his times” – this is the official word on Jefferson’s relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings: “The claim that Thomas Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings, a slave at Monticello, entered the public arena during Jefferson’s first term as president, and it has remained a subject of discussion and disagreement for two centuries. Based on documentary, scientific, statistical, and oral history evidence, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) Research Committee Report on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings (January 2000) remains the most comprehensive analysis of this historical topic. Ten years later, TJF and most historians believe that, years after his wife’s death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson’s records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston Hemings.”

Let me start with what has been deemed as historical record. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation – which not only owns and operates Jefferson’s legendary home, Monticello, but maintains the most comprehensive website focused on “Monticello, Jefferson, his family, and his times” – this is the official word on Jefferson’s relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings: “The claim that Thomas Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings, a slave at Monticello, entered the public arena during Jefferson’s first term as president, and it has remained a subject of discussion and disagreement for two centuries. Based on documentary, scientific, statistical, and oral history evidence, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) Research Committee Report on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings (January 2000) remains the most comprehensive analysis of this historical topic. Ten years later, TJF and most historians believe that, years after his wife’s death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson’s records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston Hemings.”

That the man who wrote the very words of the Declaration of Independence – “all men are created equal” – not only kept slaves (he owned some 600 human beings during his lifetime), but even fathered at least six slave children, has been a “Paradox of Liberty” for hundreds of years. [If you’re interested in finding out more, be sure to check out the online exhibition, presented by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, in partnership with TJF.]

Author Kimberly Brubaker Bradley meticulously takes Jefferson’s history as it was officially recorded at the time of her writing – while clearly acknowledging that historical evidence is not immutable – and creates an unforgettable story (soulfully read by Adenrele Ojo who correctly says ‘Monti-cello‘ like the instrument!) of the complicated relationships within a significant, mixed-race family. Sally Hemings’ children are a secret that everyone in Monticello knows, but no one ever acknowledges: her four surviving children – three sons and one daughter – call their father “Master Jefferson,” just as all the other plantation slaves must do.

Focusing on three characters – including Jefferson’s sons Beverly and Madison – Bradley imagines the lives of the slave children, growing up – and serving – their white relatives; although protected from the worst hard labors, Jefferson’s own progeny are hardly “created equal.” To contrast the comparatively easier lives of Jefferson’s children, Bradley chooses as her third protagonist another (historically documented) plantation child, Peter Fossett, who, unlike Beverly and Maddy can openly love, admire, live with his father, but will be subjected to watching his family splintered and sold.

Intended for younger readers, Bradley navigates admirably through challenging territory, voicing the confusion children must confront in a senseless world they are born into, that they cannot possibly understand. Sally must explain the incomprehensible, conflicting laws that make her children both white (seven of their eight great-grandparents were white – which in itself is a heinous history) and slaves (the child of a slave is also a slave) at the same time. She must prepare at least two of her children for their white destinies by age 18, at the cost of losing each forever … to freedom.

Whether read as history or fiction, Sons is an unflinching look at America’s tragic enslaved past. As African American History Month begins this week, Bradley’s enlightening, fascinating novel is an extremely timely reminder that “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” are hard-won “inalienable rights” meant for one and all.

Readers: Middle Grade, Young Adult, Adult

Published: 2011