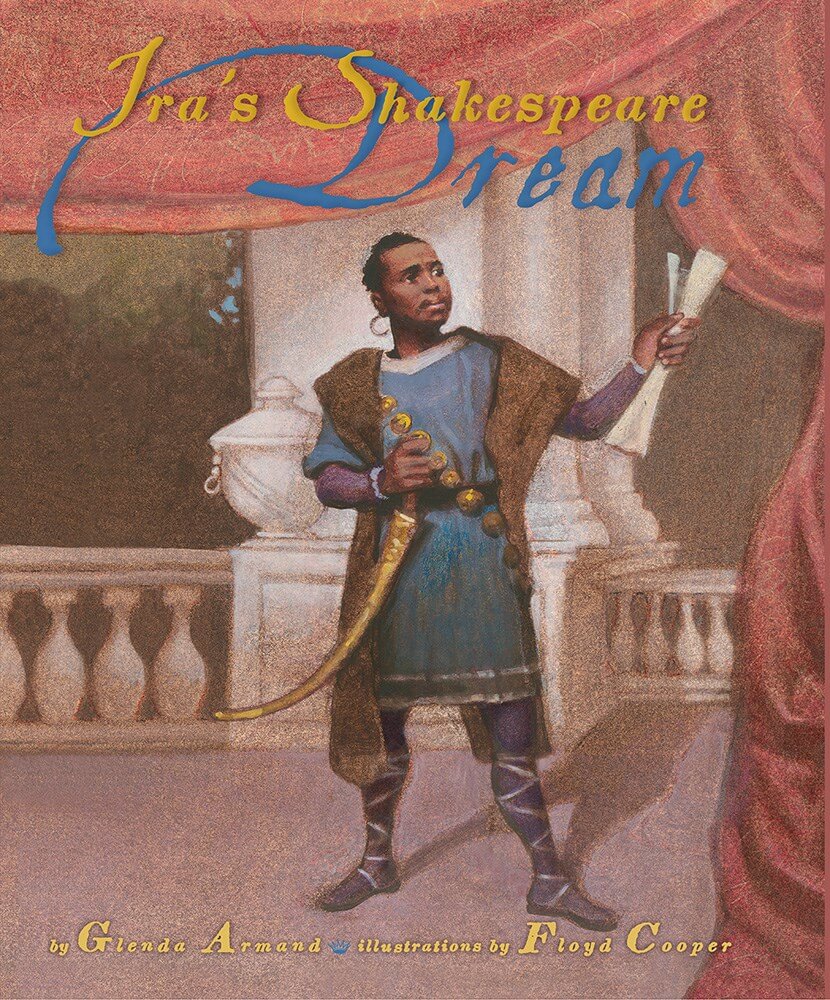

27 Oct / Ira’s Shakespeare Dream by Glenda Armand, illustrated by Floyd Cooper

When their own country wouldn’t allow American artists of color the freedom of expression, many found stupendously appreciative audiences on distant shores, including such entertainment legends as dancer/singer Josephine Baker and actor Anna May Wong. Europe, and parts of Africa and Asia, welcomed expatriates-of-color throughout the 20th century, where they were able to escape the racism, segregation, and limited opportunities that defined them at home.

When their own country wouldn’t allow American artists of color the freedom of expression, many found stupendously appreciative audiences on distant shores, including such entertainment legends as dancer/singer Josephine Baker and actor Anna May Wong. Europe, and parts of Africa and Asia, welcomed expatriates-of-color throughout the 20th century, where they were able to escape the racism, segregation, and limited opportunities that defined them at home.

Rewind a century further back to the early 1800s when most African Americans were still enslaved throughout the United States. In New York City, young Ira Aldridge dreamed of becoming a Shakespearean actor. While his teacher at the African Free School recognized Ira’s gift, he was also realistic about the future: “‘You dream too big for a colored boy.’” The teacher encouraged Ira to become a teacher and “‘use [his] great talent to inspire the younger students.’” So, too, Ira’s widowed father insisted his son become a minister like himself, “‘to preach about right and wrong.’”

Frustrated at home, and encouraged by his older brother to seek “an adventure,” Ira found a job as a cabin boy on a cargo ship. The captain protected Ira from being sold in South Carolina, but for the rest of his life, Ira would never forget the inhumane agony of witnessing slavery.

More determined than ever to achieve his “Shakespeare dream,” Ira found odd jobs at the African Grove, a newly established “all-black theater in New York City,” and eventually found himself on the stage. Employed by two actor brothers returning to London, 17-year-old Ira landed in England in 1824 full of joy and promise: “‘I am following in Shakespeare’s footsteps!”

On stages throughout England and Europe, Ira found the adulation and success he could never have had at home. As his teacher had wanted him to teach, and his father to preach, Ira fulfilled those expectations, as well: he never forgot his experiences in the South and often educated audiences about the evils of slavery, as well as supported abolitionists from abroad. His dream never wavered as he became “one of the greatest Shakespearean actors of the nineteenth century.”

Following the resonating journey she created in her 2011 debut, Love Twelve Miles Long, author Glenda Armand captures Ira’s odyssey not only in succinct, dramatic lines, but also manages to weave in some of Shakespeare’s best-known verses with perfect timing throughout. Her co-star artist Floyd Cooper’s use of pointillism evokes an air of centuries-old history, complementing and enhancing Armand’s text with evocative scenery and eloquent depth.

Two centuries have passed since Ira Aldridge was an excited schoolboy bursting with bold tenacity. Alas, for American actors of color, equitable progress still has much to grow: only just last month, Viola Davis made history as the first-ever African American woman to win an Emmy for best actress in a drama series. Her spot-on acceptance speech was especially award-worthy: “In my mind, I see a line. And over that line, I see green fields and lovely flowers and beautiful white women with their arms stretched out to me over that line, but I can’t seem to get there no how, I can’t seem to get over that line.

“That was Harriet Tubman in the 1800s. And let me tell you something – the only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity. You can not win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there.”

Ira Aldridge had to leave home to seek his opportunities. Even in the 21st century, such voyages out still happen. Thankfully, progress continues – albeit still slowly – as more and more American performers continue to fight for and reach their own lofty dreams.

Readers: Children

Published: 2015