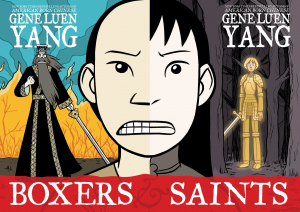

20 Sep / Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang, color by Lark Pien

In 2006, Gene Luen Yang made major literary headlines when his then-debut, American Born Chinese, became (not without controversy, ahem!) the first-ever graphic novel nominated for a National Book Award. [Click here for my 2007 post-NBA interview with Yang.] Released earlier this month, Yang’s two-volume Boxers & Saints returns him to the recently announced NBA Young People’s longlist. Allow me a moment to whoop and holler in congratulatory glee …

In 2006, Gene Luen Yang made major literary headlines when his then-debut, American Born Chinese, became (not without controversy, ahem!) the first-ever graphic novel nominated for a National Book Award. [Click here for my 2007 post-NBA interview with Yang.] Released earlier this month, Yang’s two-volume Boxers & Saints returns him to the recently announced NBA Young People’s longlist. Allow me a moment to whoop and holler in congratulatory glee …

Although packaged as two separate titles, both should be read together to maximize insight and enjoyment. You wouldn’t be satisfied with half a story, right?

“Every war has two faces,” the back covers of both titles aptly insist. During the foreign-incited Boxer Rebellion in 1890s China, the eponymous Boxers are represented by a young boy named Little Bao, who is more interested in the epic stories of the traveling Chinese operas than the hard labor needed to keep the family farm producing; the titular Saints are led by a young girl known only by her birth order, “Four-Girl,” who as the fourth daughter in her extended family is neither welcomed nor nurtured.

Even in the remotest villages, the “foreign devils” are encroaching with both their indiscriminate guns and their proselytizing religion. Little Bao’s father falls victim to the foreigners’ violence, and the villagers realize they will need to learn to protect themselves. A mysterious man named Red Lantern appears, savior-like, and trains the young men in kung fu. Little Bao’s childhood conversations with the opera gods morphs into the constant demands of the warrior spirit of Ch’in Shih-huang, China’s first emperor who managed to unite the vast country. The emperor demands that Little Bao must keep their beloved country together – which can only be achieved by ousting not only the foreign devils, but the “secondary devils,” as well – their fellow Chinese who have fallen under the influence of Christianity.

Those Chinese Christians are the so-called Saints. They are who welcome “Four-Girl” in spite of her endless questions, recurring doubts, and demands for snacks. She finds her community – and even a name of her own, Vibiana – among those very foreign devils and their converts. She also discovers her own heroine, Joan of Arc, who both inspires and haunts her. As the Chinese vigilantes bring violence closer to her walled Christian village, she begs young Joan for guidance … and impossible answers.

Boxers, at almost double the length as Saints, is the volume to read first. Its extra page count sets up a fuller context to what happens on either side of war; it also sets up the narrative overlaps between Little Bao and Vibiana. The tragic outcome is inevitable –this is the guaranteed horror of war – but Yang’s graphic frames that fast forward to the conclusion are filled with moments of joy, discovery, empathy, soul-stirring doubt, and inexplicable resolve.

Most remarkable of all, Yang (who himself is a “secondary devil”-Christian, as well as a teacher in a Catholic high school in Northern California) gives literal face and voice to the undeniable forces that wield such terrible power over the actions and lives of young people – the war machine will not be ignored. ‘Good’ and ‘evil’ no longer exist, which ‘side’ you’re on predetermines your actions, loyalty can only be upheld with devastating choices. While the historic details here are inspired by the actual Boxer Rebellion, the underlying narrative is clearly of war – any war: the impossible demands, the illogical spin, and always, the unavoidable carnage.

Read and weep. And read and weep again. Boxers & Saints – up next, NBA shortlist? And then … history awaits …!

Readers: Young Adult, Adult

Published: 2013