23 Sep / A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers by Xiaolu Guo [in San Francisco Chronicle]

Alas, summer’s over, but that doesn’t mean the fun reads have to be thrown aside for more serious fare. If anything, some depth mixed with light fun might make for the ideal transitional book.

Alas, summer’s over, but that doesn’t mean the fun reads have to be thrown aside for more serious fare. If anything, some depth mixed with light fun might make for the ideal transitional book.

A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers by Xiaolu Guo, about a young Chinese woman who arrives in London to learn English and finds love, language and loss – about in that order – fits the bill nicely. The woman’s journey of self-discovery begins with a name change when she becomes just Z, because the Western tongue cannot manage Zhuang Xiao Qiao: “They have no idea how saying it. When they see my name starts from ‘Z,’ stop trying. I unpronounceable Ms. Z.”

Armed with her Concise Chinese-English Dictionary, a newly acquired Collins English Dictionary because it is the self-proclaimed “AUTHORITY ON CURRENT ENGLISH,” and notebooks she fills with unfamiliar words, Z proves a keen observer of life in the West. Guo captures her developing fluency through diary-like vignettes that begin not with dates but rather a single word or phrase and its definition – from “alien” to “fart” to “physical work” – entries in which Z’s voice dramatically improves from broken thoughts into complex awareness during the 13 months of her English adventure.

In school, Z is a bewildered beginner: “But, who cares a table is neuter? Everything English so scientific and problematic. Unlucky for me because my science always very bad in school, and I never understanding mathematics. First day, already know I am loser.” Outside the classroom, from “scrumpled eggs” to “filthy [fizzy] water,” to the confusion of not knowing how to “properly” close a cab door, Z is a self-described alien: “[L]ike Hollywood film ‘Alien,’ I live in another planet, with funny looking and strange language.”

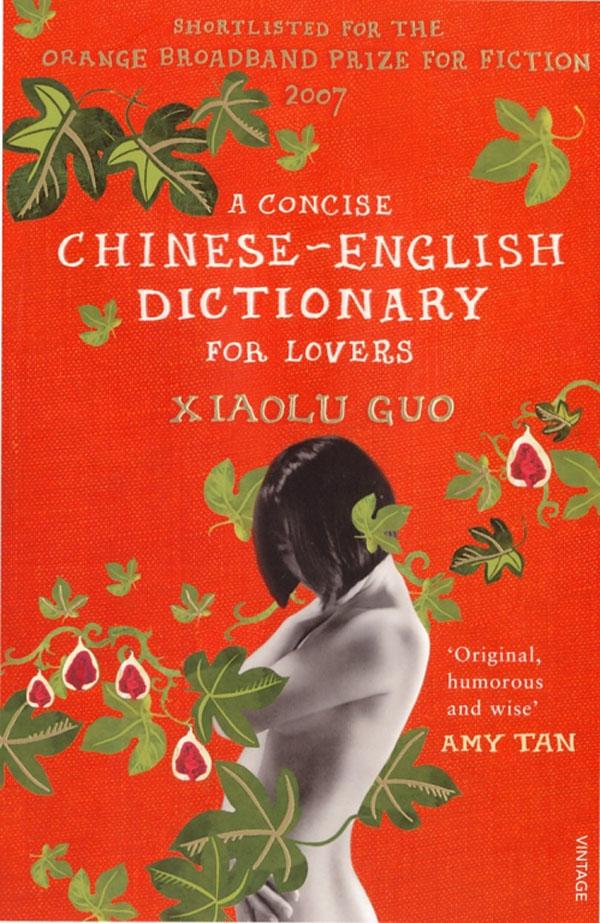

Thus begins Z’s life with the nameless “you,” a bisexual, ex-anarchist wannabe sculptor with a ramshackle home in the East London borough of Hackney. Although she continues her language classes, “you” becomes Z’s primary teacher, her de facto cultural, linguistic – and, of course – sexual ambassador in a brave new world. And, as the novel’s blatant book cover suggests, Z finds herself in a makeshift Garden of Eden – replete with figs! – which can mean only that the unavoidable fall awaits.

As Z’s language improves, “you” inevitably tires of her. Her naive curiosity becomes a burden, her emotional needs prove stifling, their cultural divide is too vast. As “you” drones on about privacy and freedom, Z compensates with exaggerated self-incriminations: “As long as one has black eyes and black hair, obsessed by rice, and cannot swallow any Western food, and cannot pronounce the difference between ‘r’ and ‘l,’ and request people without using please – then he or she is a typical Chinese: an ill-legal immigrant, badly treat Tibetans and Taiwanese, good on food but put MSG to poison people, eat dog’s meat and drink snakes’ guts.”

Longing instead to be “a citizen of the world,” Z travels solo through the European continent after much urging from “you.” Guo subtly marks September’s entries with city names rather than single words – a reminder that English is the common foreign language that Z shares with the strangers she meets along her journey. When Z returns to London, the end is inevitable (her student visa lasts a year), but not before she learns a few more words: “dilemma,” “contradiction,” “fatalism” and “departure.”

Dictionary is Guo’s third novel, and her first in English. (Her previous Village of Stone, translated from the Chinese and published in Britain, is not yet available in the United States.) Z’s yearlong learning curve could be a paradigm for Guo, who is also an award-winning filmmaker, as she herself transitions full time into English. The handwritten “Sorry of my english” facing the book’s title page proves not so much an apology but a challenge that Guo exceeds by book’s end. While Dictionary initially seems a fast, breezy read, don’t be so easily entertained as to miss the many nuances. Just like the single-word entry markers, beyond the most obvious definitions are deeper, more satisfying meanings.

Review: San Francisco Chronicle, September 23, 2007

Readers: Adult

Published: 2007