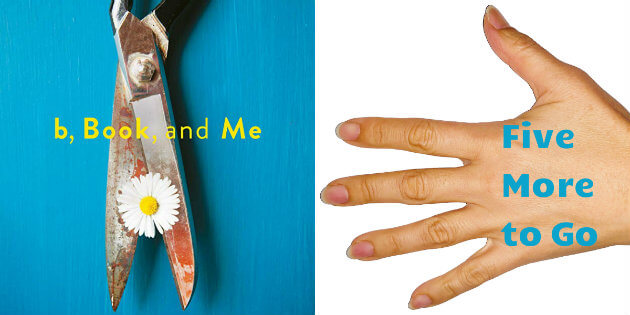

12 Feb / Five More to Go: Kim Sagwa’s b, Book, and Me [in The Booklist Reader]

b, Book, and Me by Kim Sagwa and translated by Sunhee Jeong

b, Book, and Me by Kim Sagwa and translated by Sunhee Jeong

Although this book is set in a coastal suburb outside Seoul, the cycle of neglect by stressed or careless adults can and does happen anywhere. In such an all-too-familiarly indifferent environment, lauded Korean writer Kim introduces three misfits, each struggling for their very existence: two teen girls and a socially outcast, self-isolated young man. The titular “Me” is Rang, whose disengaged parents provide financial privilege but care little about her actual well-being. Her only friend is “b,” whose family’s poverty keeps her trapped “where people who are ruined live.” In a downtown café ironically named Alone, they meet “a strange guy” named Book – who does nothing but, well, read books. Abuse and power shifts prove inevitable. At turns raw and piercing, dreamy and surreal, Kim’s latest import – urgently translated by Sunhee Jeong – is a pressing indictment of today’s too-often onerous transition toward uncertain adulthood.

Difficult coming-of-age novels are, alas, a global staple. Neglected children and missing adults – by choice or circumstance – populate these five notable titles. Surviving childhood is too often more miraculous than guaranteed.

Bad Friends by Ancco and translated by Janet Hong

Bad Friends by Ancco and translated by Janet Hong

Only the back, front, and inside covers show color here, in muted pastels. Within are black-and-white panels so disturbing and brutal that any further vibrancy might prove overwhelming. And yet, despite the horrifying, can’t-turn-away abuse, Korean comics creator Ancco manages to infuse her extraordinary portrait-of-an-artist-as-a-young-teen narrative with redemption, contentment, and – yes – even happiness. Making her English-language debut by way of award-winning Canadian translator Hong, Ancco uncompromisingly exposes societal dysfunction and punitive exploitation, especially of young women, while acknowledging and memorializing the saving power (for some) of devoted friendship.

A Girl Returned by Donatella Di Pietrantonio and translated by Ann Goldstein

A Girl Returned by Donatella Di Pietrantonio and translated by Ann Goldstein

The unnamed narrator is 13, raised by two affectionate parents in a comfortable city home where she has her own room. School, swim and dance lessons, a nearby best friend, and a house a short walk away from the sea are the life she’s known. And then, one August afternoon in 1975, she’s driven to an apartment in a small village and abandoned there to become the “arminuta, the one who was returned.” The mother she’s always known is sick, perhaps dying. Her father won’t raise her alone. She’s told, “my real parents wanted me back.” She’s now one of five children in a family who has no room for her, reduced to neglect, hunger, and occasional abuse. As she navigates her new life, she will need to learn acceptance and practice rejection in order to survive. Italian author Di Pietrantonio makes her English-language debut, thanks to Elena Ferrante translator Goldstein.

Educated by Tara Westover

Educated by Tara Westover

As the youngest of seven children born to a junkyard-tending father and midwife-herbalist mother in remote Idaho, Westover realizes at seven the single fact “that makes [her] family different: we don’t go to school.” Her family espouses Mormonism, although their practices tend toward isolated fundamentalism. Her father’s distrust of government, doctors, and education left Westover without a birth certificate or medical and school records. Neglect and abuse were common. Encouraged by a brother who left, Westover began the process of getting “educated” when she entered her first-ever classroom at 17 as a Brigham Young University freshman. Basic history – the Holocaust, civil rights movement – was yet unknown to her. She progresses to Cambridge, Harvard, and back to Cambridge, where she earns a history PhD. With steely, almost detached resolve, Westover endures and escapes.

GO by Kazuki Kaneshiro and translated by Takami Nieda

GO by Kazuki Kaneshiro and translated by Takami Nieda

Japan and Korea’s centuries-long, combative history has long made Koreans in Japan second-class citizens. Kaneshiro, who is Korean Japanese, channels his own experiences into his teenage protagonist, Sugihara, a Japan-born-and-raised ethnic Korean. Sugihara decides to transfer into a Japanese high school after attending only Korean schools. Three years later, he’s still plagued with violent rejection, and his only Japanese friend is another pariah, a yakuza’s son. And then he meets a girl, and the deeper their love, the harder it becomes to reveal his secret. The title is a homophone in Japanese for language, an honorific prefix, the number five, the strategic game, and more; these several meanings constitute a pointed reminder of the complexity of people, relationships, and identity. Translator Nieda provides gratifying Anglophone access to Kaneshiro’s searing ruminations – heightened by Malcolm X and Bruce Lee, softened by Miles Davis and Brahms – on history, xenophobia, and, of course, love.

Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All by Laura Ruby

Thirteen Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All by Laura Ruby

Ruby’s narrator – her name eventually revealed as Pearl – is dead. Pearl’s primary object of attention is not; Frankie, who’s 14 in 1941, is a “half orphan” relegated to a Chicago orphanage with her siblings by their living Italian immigrant father, who (relatively) lavishes his three children with gifts during visits – but claims he’s financially unable to bring them home. When he remarries, he further deserts his family and heads to Colorado with his shrewish new wife and her children. Disappointment, even abuse, looms for Frankie, alleviated by rare moments of mischievous fun, surprising bonds, and maybe a chance at first love. While Pearl observes others, she intertwines glimpses of her own corporeal life of victimization and abandonment. “Three or ten or thirteen doorways, there are wolves behind them all,” one of Pearl’s ghost friends intones, but resilience and strength will propel both teens to open the doorways and confront the necessary challenges to move forward toward freedom.

Published: “Five More to Go: Kim Sagwa’s B, BOOK, AND ME,” The Booklist Reader, February 11, 2020