My name is Harry Lee Chow. I was born in 1950 in Washington, D.C. Growing up in the area, I grew up in an all-Black neighborhood. And that’s why some people say I have a Southern accent—because I grew up with Black folks that all came from the South, and they come from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, all around that area. But being Chinese, living in an all-Black neighborhood was not always a good experience. I had plenty of good Black friends, but there’s quite a few Black folks that always reminded me that I was different. And it got to the point where my mom and dad, we’d be walking down the street or around the neighborhood, and I’d tell them, “Don’t speak Chinese, they’re gonna make fun of us.”

And so, at that time period, I was not proud to be Chinese. I just felt out of place because I was always reminded that I was different. I got in a fight a few times—I didn’t know how to fight. I would just swing, you know. I got in a fight a few times and I got jumped by like four guys at one time. And I didn’t know how to fight, but I got beat up. Well, my Sunday school teacher handed me this book. I think I was talking to him about being bullied on, and he gave me this book on karate, and he said, “Just check it out.” He said, “These are fighting techniques from Asia. It’s Japanese, but it’s good to learn.”

I looked at it. I didn’t study it in depth, but I looked at it to understand the movements. And I didn’t quite understand it because nobody taught me. And through my father and him, I think I heard the term gong fu—because the Cantonese call it gong fu, the Mandarin call it kung fu, but kung fu is what most people know it by. And actually gong fu and kung fu means “working man”—working man to the point where you hone a skill. And it just sort of referred to the martial arts indirectly, because that’s what you gotta do in order for your skills to mature to a higher level.

And so it wasn’t until I was in high school, when I went to McKinley Tech. It was by happenstance—I was walking in the hallway going towards the gym, and I saw a crowd in the hallway looking at this guy, and I was looking at him and he was doing martial art movements. And I looked at him, and he looked at me, he noticed I was Asian. And he started talking to me, and I told him I was Chinese, and [he] said, “Oh yeah, I practice kung fu.” I said, “What?” My eyes lit up and we started conversing. He invited me to practice with him, and I got to know Josephus Colvin, his nickname is Kung Fu Joe. And so I started practicing with him at Banneker [High School]. It was a loose group of us: Spanish Joe, Jimmy, Kung Fu Joe, and William Brooks. We used to all hang out together and work out whenever we can. Rock Creek Park, Meridian Hill Park, or Malcolm X Park, or some other park. I worked out with friends at Turkey Thicket [Recreation Center] and other places.

So we had a lot of informal workouts in somebody’s backyard or a parking lot. And through William Brooks, we started working out with Robert W. Smith—he taught Tai Chi. He was a marine guy that worked at—I think it was either the CIA or FBI, but I think it was CIA—and he lived in Bethesda, Maryland. And he worked out every Saturday morning at the YMCA. And he also taught us basic Shaolin form, the basic Ying Yi or Xing Yi and Ba Gua form. So we just practiced whatever we could. We worked out at various areas in Rock Creek Park, Kung Fu Joe and I, and what happened was, he was talking to me about Bando. Bando is Burmese karate. And, and he mentioned that Mas Nishida was the sensei, or the teacher, and Hoy Kew Lee was his assistant.

My friend Lester Lee went to school with Hoy Kew and he said Hoy Kew would get into a lot of fights at school. And when I talked to Hoy Kew about it, he said, “Yeah, we need to learn.” That when he learned a technique, you wanna try it out, he’d pick a fight with somebody. And, I went to a lot of tournaments with Hoy Kew when we were in Bando—and that guy can fight! He was a good fighter. And even Kung Fu Joe said, “You gotta look at that guy. Watch him fight.” And when he sparred in class, in Bando class, I watched him fight. I watch him, watch his technique and go to tournaments. I remember he had this really fast sidekick when anybody tried to charge in at him. His sidekick would shoot right out and stop him. I mean, really fast sidekick. But anyway Hoy Kew could fight.

He opened up a school on I street—I forgot the address—but it was I street near Chinatown, a block away from Chinatown. So we worked out there and it was Hoy Kew that taught there. He taught there for one year—maybe a year or beyond a year—because when I was there, I learned Little Tiger, Flowery Fist, Gong Lik. I learned a Broad Sword form, and I started on a Stick form, and I learned a little bit more than half of it. And then a year or so later, Dean Chin came aboard and he took over and Hoy left. And so that was my form in terms of working out with all the Kung fu and karate people at that time period. It’s amazing to me that Chinese culture created such a unique and interesting fighting style.

And I like doing it not because—I don’t want to be a killer, I don’t want to fight anybody. I like it for self-defense, but mainly because it’s a beautiful art. It’s intricate. The movements are beautiful. I like the hand movements, the kicks—the tornado kicks, the swallowtail kicks—and every style is unique. I like looking at the southern style, the southern hand techniques, like in Wing Chun. And they’re unique and practical. Each style has a different theory of how to do things. Like the Wing Chun style, they have the center line: You fight from the center line and certain angles. And you look at the Hung Gar style, they use animal techniques and it’s hard to use. It’s more muscular. And then you look at the northern style, they have more sweeps, jumps kicks, wide sweeping movements—beautiful movements, very acrobatic—and that’s why you see a lot of it in Chinese opera. Some styles emphasize mostly hands, and others a combination of both. And some styles just emphasize low kicks, to middle, to the hip area, to the lower legs, and others high above, to the head. A lot of styles have over 20 forms—that’s a lot of freaking forms! But no style is the end-all-be-all. No style has all the answers. Every style is unique.

And also I found out throughout the years that no style is pure, every style evolves. I don’t think Wing Chun looked like it does in modern times [the way] it did a few hundred years ago, or some other style like Tiger and Crane. So no style is pure. They always seem to be evolving. So you know, I like doing that because it keeps me in touch with my culture. I guess it makes me feel Chinese. And so what I found was that since kung fu became so popular, especially with the appearance of Bruce Lee, a lot of people, especially young kids, they respect kung fu. And I found that a lot more Black friends that understand kung fu appreciate the Chinese culture because of it.

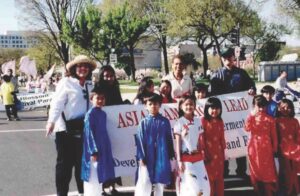

Harry Lee Chow is a photographer, documentarian, and community activist who was born in D.C. and grew up on North Capitol Street NW. As kids, he and his siblings helped out in the family laundry and attended McKinley Technical High School in the 1960s. Residing about a mile from Chinatown, the family was connected to neighborhood organizations and activities like the Lee Family Association and the Chinese Community Church. Harry himself worked at Chinatown Tropicals, an aquarium supply store on H Street; as well as with a number of neighborhood and community development groups organized in the 1970s, including the Chinatown Courtesy Patrol, Chinatown Creative Workshop, and Eastern Wind collective. Harry earned his degree in art and art history from the University of Maryland College Park. Afterwards, he worked for 24 years at the D.C. National Aquarium, which was located in the basement of the U.S. Commerce Department.

A lifelong martial arts enthusiast, Harry grew up learning martial arts moves in the school yard and city parks and Chinatown—training in Burmese Bando, Kung Fu (Jow Ga, Hung Gar Tiger Crane, Seven Star Praying Mantis), and Tai Chi. He attended events across the mid-Atlantic region and collected the early English-language books and magazines that fostered the growing popularity of Asian martial arts in the 1960s and 1970s. He is also a photographer, who has documented and stewards an impressive collection of images and ephemera related to martial arts, D.C. Chinatown, and the Chinatown community dating back to the late-1960s.

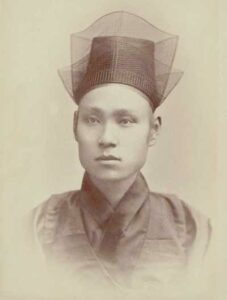

Harry Lee Chow with his martial arts friends Bradley Holland, Mike Arrington, Jimmy Yee, Donald Yee, about 1974.

For decades, Harry Chow has documented the history and evolution of martial arts in Washington, D.C. Sightlines dedicates an entire section to this history, and prominently features objects from Chow’s collection including this photo of him as a youth with his friends.

Photo courtesy of Harry Lee Chow