Traditionally, lion dance involves costumes, movement, and music made with drums and gongs. It has been performed in Washington, D.C., since World War II, and has been a means through which ethnic Chinese immigrants have preserved and shared their cultural heritage.

Lion dance is a Chinese cultural tradition that is performed to chase out bad energy, herald in good fortune, and express respect. The first lion dance performance in D.C. was organized by the Chinese Youth Club in the 1940s. They continue the tradition today along with multiple other lion dance teams across the D.C. metro region, including those organized by martial arts studios and Asian American student clubs at local colleges and universities. Annually, a critical mass of these groups come together in D.C.’s Chinatown for the Lunar New Year parade.

Lion dance is based in Chinese Kung-Fu techniques and movements. Each lion is animated by two people working as a team, one operates the head and the other the tail, with their steps and gestures coordinated to the rhythms of live percussion, which includes drums and cymbals along with other hand-held instruments.

In this film, you can see that the lions were performing amidst a cacophony of sound that included firecrackers exploding along the ground as well as from a long strand suspended from a yellow crane.

The Chinese Youth Club (CYC) was established in D.C.’s Chinatown in the late 1930s and today continues its founders’ legacy of engaging youth in athletics, cultural education, and volunteer activities. In the 1940s, during World War II, CYC organized the city’s first lion dance performance for a fundraising event supporting the war effort. For this, they borrowed equipment from the On Leong Merchants Association in New York City. Later, they acquired their own lions.

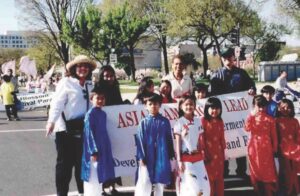

Chinatown’s annual Lunar New Year parade has been organized by D.C.’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) for about seven decades. The parade is an important celebration of the neighborhood’s history, and it is the largest and longest continuously running, community-organized Asian American public event in the city.

Multiple lion dance teams participate in the parade. During the Lunar New Year season, these groups are in high demand. They are invited to perform at parties, embassies, and schools. And businesses—both in and beyond Chinatown—invite them into their spaces to ensure a good start to the new year.

Over the years, lion dance has become an important activity signaling connections to heritage and community, as well as to place.

Hoy K. Lee was among the first teachers in DC who formally taught kung fu. It was through this and other martial arts schools that participation in lion dance began to extend beyond Chinese Americans.

Participants in D.C. martial arts communities are diverse, representing Asian and non-Asian practitioners, as well as different generations, lineages, and systems.

Formal training inthe Jow Ga kung fu discipline began in D.C.’s Chinatown in the late 1960s. Six decades later, there are now several generations of diverse practitioners of this kung-fu system in the region.

This image documents the built landscape before the Gallery Place development was constructed above the metro station at this corner. Through the decades, the public presentation of Chinese culture in such events as the annual Lunar New Year parade have played an important role in representing the historical heritage of the neighborhood in the face of redevelopment and gentrification.

Wong People Kung Fu Association procure their lions from different sources depending on their needs and available supply. It’s more cost effective though to work with suppliers in U.S. cities such as New York, New Jersey, California, and Pennsylvania.

About style and design, Wong People leader Raymond Wong explains, “Traditionally there are three main colors used for lions—red with dark accent, yellow with rainbow accent, and black with dark green accent. In design and character, they represent folk hero General Quan and his two brothersand their particular virtues and strengths.” Here, the Lion on the left is General Quan, who embodies loyalty and leadership; the one on the right is Liu Bei, who is associated with prosperity and intellect.

On the first day of the Year of the Dragon, 2024, the Wong People Kung Fu Association was invited to a restaurant in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood to bring good fortune and blessings for the coming year. Here, one of the lions reaches for a lettuce that is suspended from the roof of the building. To gain height, sometimes one lion dancer will balance on the shoulders of the other.

The Wong People’s schedule on this day includes visits to restaurants around the greater D.C. metropolitan region, as well as in Chinatown, and later a private party in the suburbs.

On the eve of the Lunar New Year in 2016, the Wong People Kung Fu Association brings out their lion to visit Chinese American homes in the Shaw neighborhood.

In addition to its formal public presentation in parades, festivals, and stage performances, lion dance also continues to be an important tradition in more ritual community settings, such as when groups are invited to provide “blessings” at residential and commercial sites or for important life cycle events, such as weddings and funerals.

CYC lion team performing in Chinatown

Sightlines explores the importance of many martial arts traditions, including Lion Dance, to forming community bonds in Washington, D.C., and across the nation. Many of the images featured in this chapter are on display in the museum exhibition, including this photo of the Chinese Youth Club lion dancers during the 1972 Lunar New Year parade.