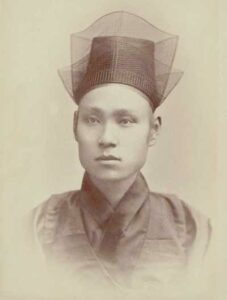

Sŏ Kwangbŏm was one of the earliest Koreans to settle in the United States and was highly influential in nurturing American understanding of Korea and its culture, especially in the nation’s capital. As a well-educated Korean from a notable aristocratic family, Sŏ was determined to free Korea (then governed by the 500-year-old Chosŏn dynasty) from the isolationism that had held back development of Western-style modernity. which Japan had embraced decades earlier.

Sŏ first visited D.C. in 1883 as part of a group of Koreans, members of the Progressive Party, sent by the Korean king on a special mission to explore the United States soon after the United States and Korea signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce (the Shufeldt Treaty) in 1882. They were accompanied by the famous American astronomer Percival Lowell (1855–1916) and a member of the American Navy, Ensign George C. Foulk (1856-1893). Another member of the group was Pyŏn Su 邊燧 (aka Penn Su, 1861–1891), who later became the first Korean graduate of an American college (Maryland Agricultural College, now the University of Maryland). The group traveled to several major American cities and even met President Chester Arthur in New York City, then split into two smaller groups, with Sŏ returning to Korea via Europe. But Washington, D.C. had made a strong impression on Sǒ, and he later chose to return.

Back in Korea, Sŏ and his colleagues in the Progressive Party pursued their goal of modernizing Korea, even taking control of the government for three days in late 1884. Sŏ, Pyŏn Su, and a few others then fled Korea, eventually arriving in the United States in June 1885. Pyŏn Su graduated college in 1891 and went to work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, where he published a survey entitled “Agriculture in Japan.” Unfortunately, he died in October 1891, struck by a train in what is now College Park, Maryland.

As it happened, another adventurous member of the U.S. Navy, Ensign J. B. Bernadou (1858-1908) had been assigned to Korea between 1883 and 1885. There he gathered a large collection of Korean artifacts and later presented them to the Smithsonian Institution. After a few other, smaller collections were added, Sŏ Kwangbŏm and Pyŏn Su worked to describe and catalogue these important early repositories of Korean culture for the benefit of Americans, especially those fortunate enough to be located near D.C.

By 1888, Sŏ Kwangbŏm had settled in D.C. and found employment of various sorts, including in the Bureau of Ethnology (probably working on the Bernadou materials), until he obtained a regular, if underpaid, job in the Bureau of Education, located in the building that now houses the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery. He made many friendships in D.C., and newspaper reports indicate that he was highly regarded. In 1892, Sŏ became a naturalized U.S. citizen while retaining his deep interest in his country of origin.

At the Bureau of Education, Sŏ’s work caught the attention of an important staff member, Anna Tolman Smith (1840–1917), an expert on foreign educational systems. The Bureau published Sǒ’s article, “Education in Korea,” in 1891. Likely because of interests shared with Smith, Sŏ also published some Korean children’s stories in 1893.

Despite having lived in the United States for nine years and taken American citizenship, Sǒ Kwangbǒm was not forgotten in his native country. He was invited back to Korea—where the political situation was in constant turmoil—in 1894 and appointed to the government post of Minister of Justice and later also Minister of Education. In 1895, he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States, and on his return to the Korean Legation in D.C., the Washington Post (Feb. 16, 1896) reported that Sǒ had arrived and had “a host of friends in Washington, who are gratified at his return here under such auspicious circumstances. The diplomatic post in this city has been vacant for some time.” No longer a low-level employee of the Bureau of Education, Sŏ presented his formal diplomatic credentials to President Grover Cleveland the next week.

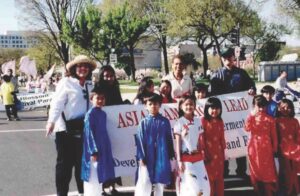

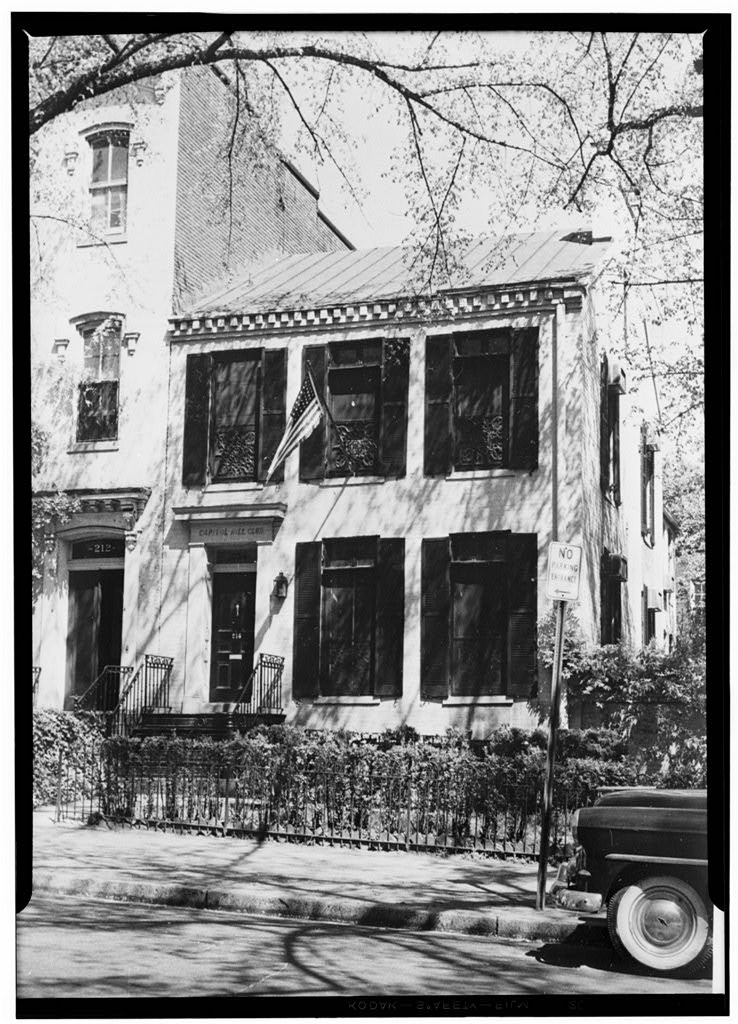

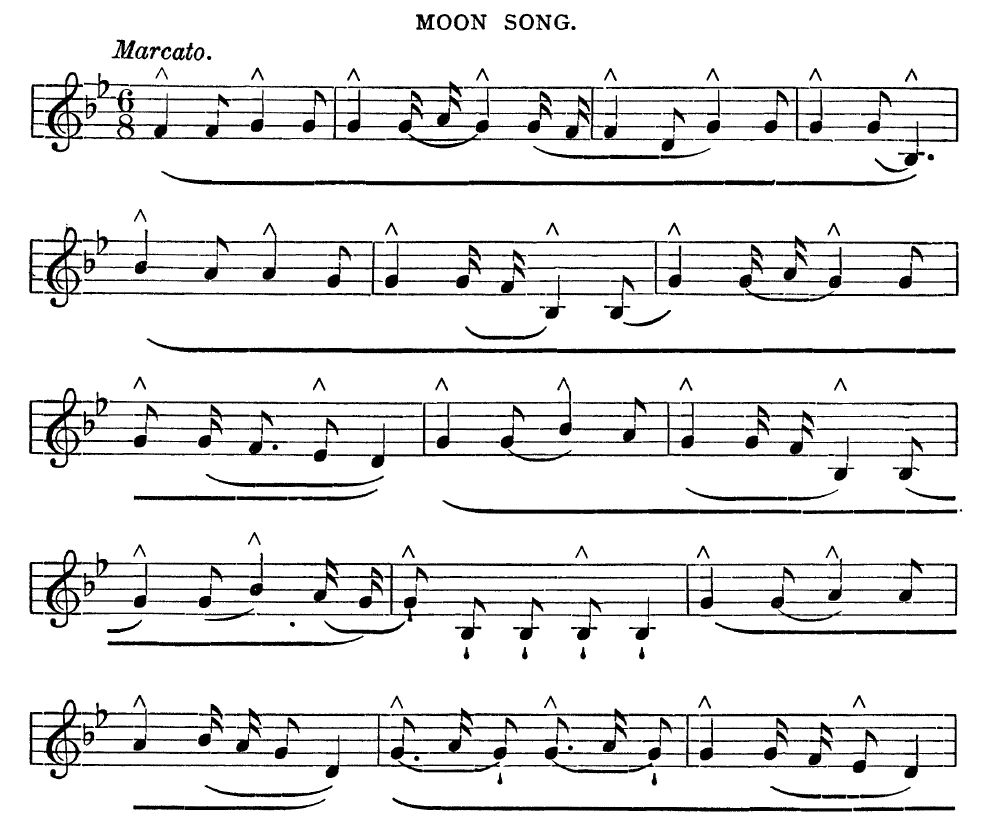

Just a few weeks later, a group of seven Korean students, who had been sent to Japan for study, arrived by ship in Vancouver, British Columbia, penniless and with no English. Sŏ Kwangbŏm arranged for them to come to D.C. and found them accommodation and educational opportunity at Howard University. A remarkable story followed: Anna Tolman Smith arranged with her close friend Alice Cunningham Fletcher (1838–1923), an anthropologist with a rare Edison wax cylinder recording device, to record two of the students and Sŏ himself singing. The recording was made at Alice Fletcher’s house near the Capitol building on July 24, 1896, and the resulting six cylinders are the earliest sound recordings of Korean voices, including children’s songs, now still preserved in the Library of Congress. The next year, Anna Tolman Smith published an article in the Journal of American Folklore entitled “Some Nursery Rhymes of Korea,” largely based on these recordings and, no doubt, what she had learned from Sŏ. The recent rediscovery of these recordings caused quite a stir in Korean traditional music circles, and the Korean Broadcasting System even produced a documentary on the subject in 2010.

Politics back in Korea continued to be in flux, and Sŏ was replaced as Minister in D.C. by Yi Pŏmjin 李範晉 (1852–1910), a political foe, in September 1896, only a few months after he had been assigned to that position. Sŏ remained in his adopted country, of which he was a naturalized citizen, never returning to Korea, where he would have been in considerable danger. He justified this decision on grounds of ill health (he had chronic tuberculosis), though he managed to travel to England for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in June 1897 as one of only a few representatives from Korea. A little more than a month after his return to the United States, Sŏ took a vigorous bicycle ride that aggravated his condition, and he died on Friday August, 13, 1897, having lived a remarkably varied, difficult, and influential thirty-eight years.

Sŏ Kwangbŏm’s passing was noted by many American newspapers, and Anna Tolman Smith, Sŏ’s steadfast friend and confidant for many years, wrote a heartfelt tribute to him in October 1897 for The Independent, “The Mission of Pom K. Soh,” recalling many details of Sŏ’s life and achievements, especially contributions made during his time in D.C.

Robert C. Provine is Emeritus Professor, School of Music at the University of

Maryland. He holds a B.A., two M.A. degrees, and the Ph.D. from Harvard

University. He researches the music of East Asia (China, Korea, and Japan), with

a particular focus on Korean traditional music. He taught from 1978 to 2000 at

the University of Durham in the United Kingdom, where he rose from Lecturer to

full Professor and Chair of the Department of Music. He has served as President

of the Association for Korean Studies in Europe (1993-95) and as President of

the Association for Korean Music Research (1996-2000). He contributed the

country article “Korea” and numerous shorter entries to the second edition of

the /New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians/ (2001), and he is the author

of /Essays on Sino-Korean Musicology: Early Sources for Korean Ritual Music/

(1988), plus many articles in various academic journals.

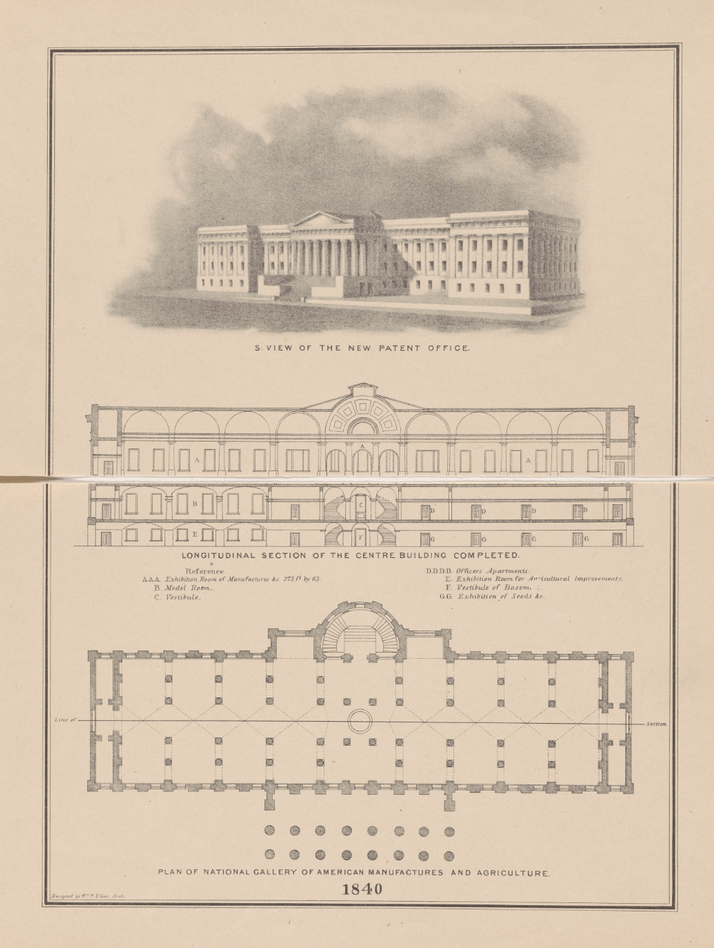

Old Patent Office Plan

The Smithsonian American Art Museum, where Sightlines is presented, is in the Old Patent Office Building. From 1852 to 1917, this building housed the Department of the Interior, which included the Bureau of Education, where Sŏ Kwangbŏm once worked as a clerk, translator, and interpreter.