Celebrating

K.W. Lee

Godfather of Asian American Journalism

Left: K.W. Lee speaks at the LA Riots panel discussion at the AAJA convention in Los Angeles, California on August 7, 2010. Credit: Photo © Hyungwon Kang. Right: This Sacramento Union article, written by K.W. Lee and Stephen Magagnini, announces a new trial for Chol Soo Lee. Credit: Courtesy of K.W. Lee Family

“We are all entangled in an unbroken human chain of interdependence and mutual survival. And what really matters is that we all belong to each other during our earthly passage.”

—K.W. Lee

K.W. Lee (1928–2025) was an award-winning investigative reporter, editor, and civil rights advocate who inspired generations of journalists and community leaders. The first Korean immigrant to work as a mainstream newspaper reporter in the continental United States, Lee described his beat as spanning the “Jim Crow South to the Yellow Peril West.”

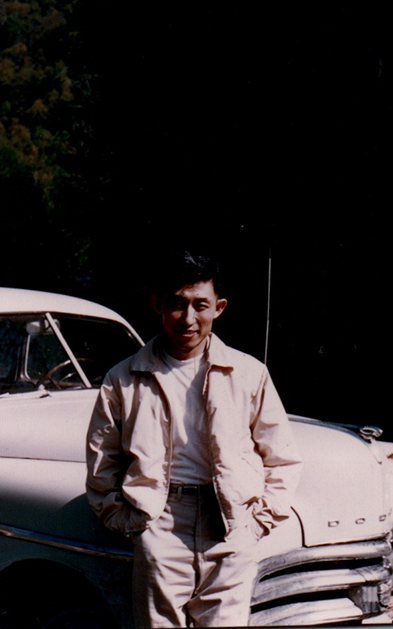

K.W. Lee poses with his car in Kingsport, Tennessee, in 1956. Credit: Collection of K.W. Lee Family.

Over a career spanning more than five decades, Lee reported for the Kingsport Times-News in Tennessee, The Charleston Gazette in West Virginia, and The Sacramento Union in California. His journalism earned over 40 awards and embodied the idea of “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” He also helmed two Korean American newspapers in Los Angeles during his storied career.

Known as “the godfather of Asian American journalism,” Lee was the inaugural recipient of the Asian American Journalists Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award and the first Asian American journalist honored with the Freedom Forum’s Free Spirit Award for his First Amendment advocacy.

Born on June 1, 1928, in Kaesong (now North Korea), Kyung Won Lee immigrated to the United States in 1950. He studied journalism at West Virginia University and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Originally hoping to bring press freedom to a newly independent Korea, he ultimately settled in the U.S. as Cold War instability dashed those ambitions.

From the late 1950s through the 1960s, Lee covered poverty, race, and political corruption in Appalachia. At The Charleston Gazette, he lived with families in rural West Virginia for a series on life in the hollows, and uncovered election fraud in Mingo County that led to federal indictments. “The day K.W. Lee left for California, the people wept,” recalled Huey Perry, former director of the Mingo County Economic Opportunity Commission.

In 1970, Lee joined The Sacramento Union as its chief investigative reporter. Described as a “heat-seeking missile” by editor Ken Harvey, he exposed dangers at nuclear power plants, inflated state pensions, and the struggles of Asian American communities—from Filipino laborers to newly arrived Vietnamese refugees.

In Sacramento, Lee pursued one of the most important stories of his life. Over nearly six years in the 1970s and ’80s, he wrote 120 articles about Chol Soo Lee, a Korean American wrongfully convicted of a 1973 San Francisco murder and sentenced to life in prison. Lee’s coverage galvanized one of the first pan-Asian American social justice movements, leading to Chol Soo Lee’s acquittal. Ranko Yamada, a leader in the movement to free Chol Soo Lee, praised the “genius in [K.W. Lee’s] writing” that made a complex case easier to understand. His articles, she said, made Chol Soo Lee—who would spend a total of 10 years in California prisons, including on death row—a real person, “somebody like in your own family or, ‘It could be me.’”

K.W. Lee, at his desk in the Sacramento Union newsroom, early 1980s. Credit: Collection of the K.W. Lee Family.

This Sacramento Union article, written by K.W. Lee and Stephen Magagnini, announces a new trial for Chol Soo Lee. Credit: Courtesy of K.W. Lee Family

In 1979, Lee co-founded Koreatown Weekly, one of the first English-language Korean American newspapers. He later edited The Korea Times English Edition. During the 1992 Los Angeles unrest, while hospitalized with liver failure, Lee continued to edit copy and guide coverage spotlighting Korean American merchants and interethnic tensions. He promoted cross-community understanding through editorial partnerships, including with the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Even after his retirement in 1994, Lee remained active—writing commentaries, lecturing, mentoring, and reminding young people of their responsibilities to speak up, share their stories, and be accountable to their communities.

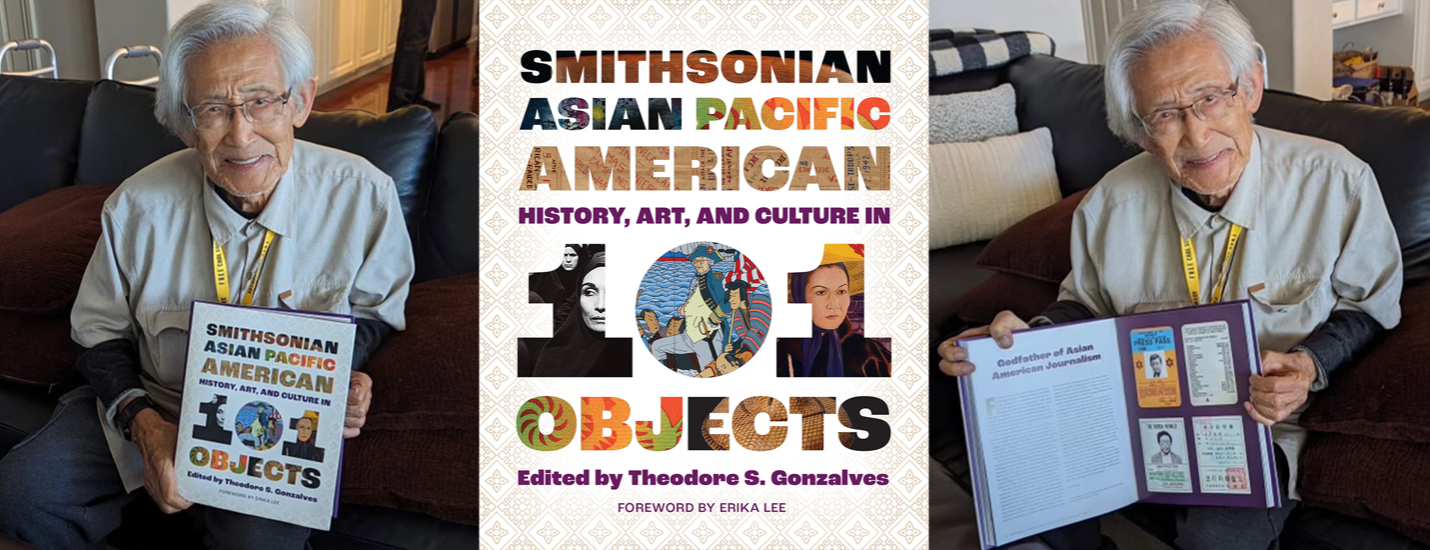

K.W. Lee in APA 101

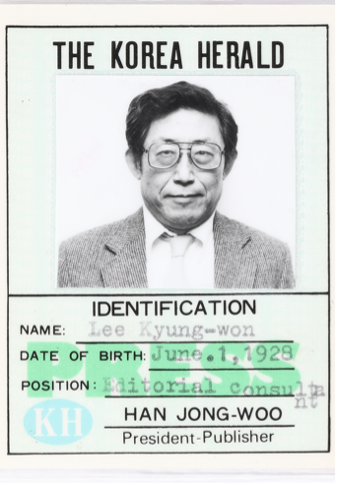

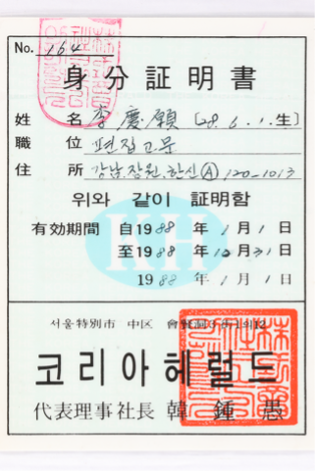

A chapter in APAC’s publication, Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History, Art, and Culture in 101 Objects, features Lee and his contributions to journalism. Lee is pictured above holding a copy of the book, opened to the spread discussing his press IDs.

In the chapter, curator Sojin Kim explains:

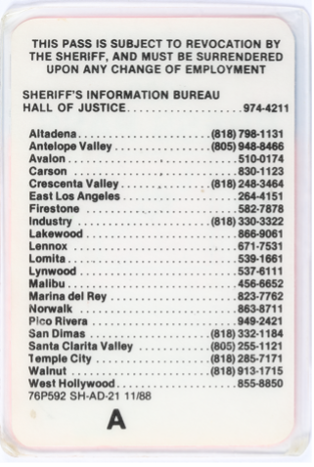

For reporters, press IDs are both indispensable tools of the trade and part of their professional wardrobe. In the old days, they tucked them into the bands of the bands of their fedoras when out on assignments. Today, they string them around their neck from lanyards. A specific type of reporter’s ID is the law enforcement press credential. These provide reporters access behind police lines, onto crime scenes, and into courthouses and prisons—all of which were the occupational stomping grounds of journalist Kyung Won Lee, aka K.W. Lee (b. 1928).

K.W. Lee’s press badges are in the permanent collection of the National Museum of American History. Pictured above are two examples.

The Ballad of K.W. Lee

The big boss of Mingo, with fire in his eyes,

Summoned his minions, spitting out lies.

A Charleston Gazette waved in his hand,

A stranger had come to expose their land.

“Look what this foreigner dares to say,

He calls us corrupt, he won’t go away.

He’s siding with Perry, with Kinderman too,

Governor Smith warned,this man must be through!”

But K.W. Lee was a fearless soul,

With pen in hand, he’d take his toll.

Through hollers and hills, with the warriors of poor,

He uncovered the rot, he opened the door.

He saw the bosses, the coal men behind,

Enslaving the people, stealing them blind.

Yet hope was rising in Mingo’s veins,

Through community action, they broke their chains.

Then came the fraud, thick as the air,

The dead cast votes, was anyone there?

Thirty thousand names on the voter rolls,

Yet the county held fewer living souls.

The people rose, they would not abide,

With courthouse records, the truth they pried.

Thirteen thousand ghosts were erased from the books,

And K.W. Lee stood fearless, despite the crooks.

They summoned him now, but not as a friend,

Death threats whispered, they wanted his end.

Yet by the county line, a guard stood tall,

The people protected the man who told all.

Then the headline rang like a hammer’s might:

“Voter Fraud in Mingo Exposed Tonight!”

The nation saw, and the bosses fell,

Indicted by law, their empire quelled.

But K.W. Lee, his job was done,

He left for the West with the setting sun.

We wept to see the warrior go,

But truth had struck its final blow.

Today, I mourn, my old friend’s gone,

But his name still rings, like a battle song.

For in Mingo’s hills, when corruption’s near,

A whisper sounds, his name is clear.

K.W. Lee, truth in the dark,

A fearless soul, a guiding spark.

Huey Perry was the director of the Mingo County Economic Opportunity Commission project in the 1960s and worked with K.W. Lee on anti-poverty issues (Cabell County/Huntington, West Virginia). He wrote this poem in honor of K.W. Lee.

K.W. Lee on assignment for an article about rural poverty, Kanawha County, West Virginia, 1969. Photo by Lew Raines/Courtesy of K.W. Lee Family.

K.W. Lee with his wife Peggy (née Flowers) Lee on their wedding day, West Virginia. Collection of K.W. Lee Family.

Select Additional Resources

Learn more about Lee’s life and legacy:

- The K.W. Lee Center for Leadership was founded by Do Kim, a civil rights lawyer, and one of the many people mentored by K.W. Lee, in 2003. Based in Los Angeles’s Koreatown, the organization nurtures high school and college students—future leaders—with his principles of truth, justice and community consciousness.

- Lonesome Journey: The Korean American Century, co-produced with Luke and Grace Kim, is an unpublished oral history project of early Korean immigrants with an emphasis on women. Dr. Edward T. Chang (U.C. Riverside, ethnic studies and Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies) translated the collection into Korean, and it was published by Korea University Press (Seoul) in 2016.

- Freedom Without Justice: The Prison Memoirs of Chol Soo Lee (Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 2017) was edited by Dr. Richard Kim, professor of Asian American Studies at University of California, Davis. He was compelled by K.W. Lee to share the largely forgotten story of Chol Soo Lee with new audiences through this volume.

- Free Chol Soo Lee, a 2022 Emmy-award-winning feature documentary directed by Julie Ha and Eugene Yi, chronicles the plight of a Korean immigrant wrongfully convicted of murder in the 1970s and the pan-Asian American solidarity movement that rallied to free him. Many credit K.W. Lee’s series of articles for sparking the landmark mobilization.