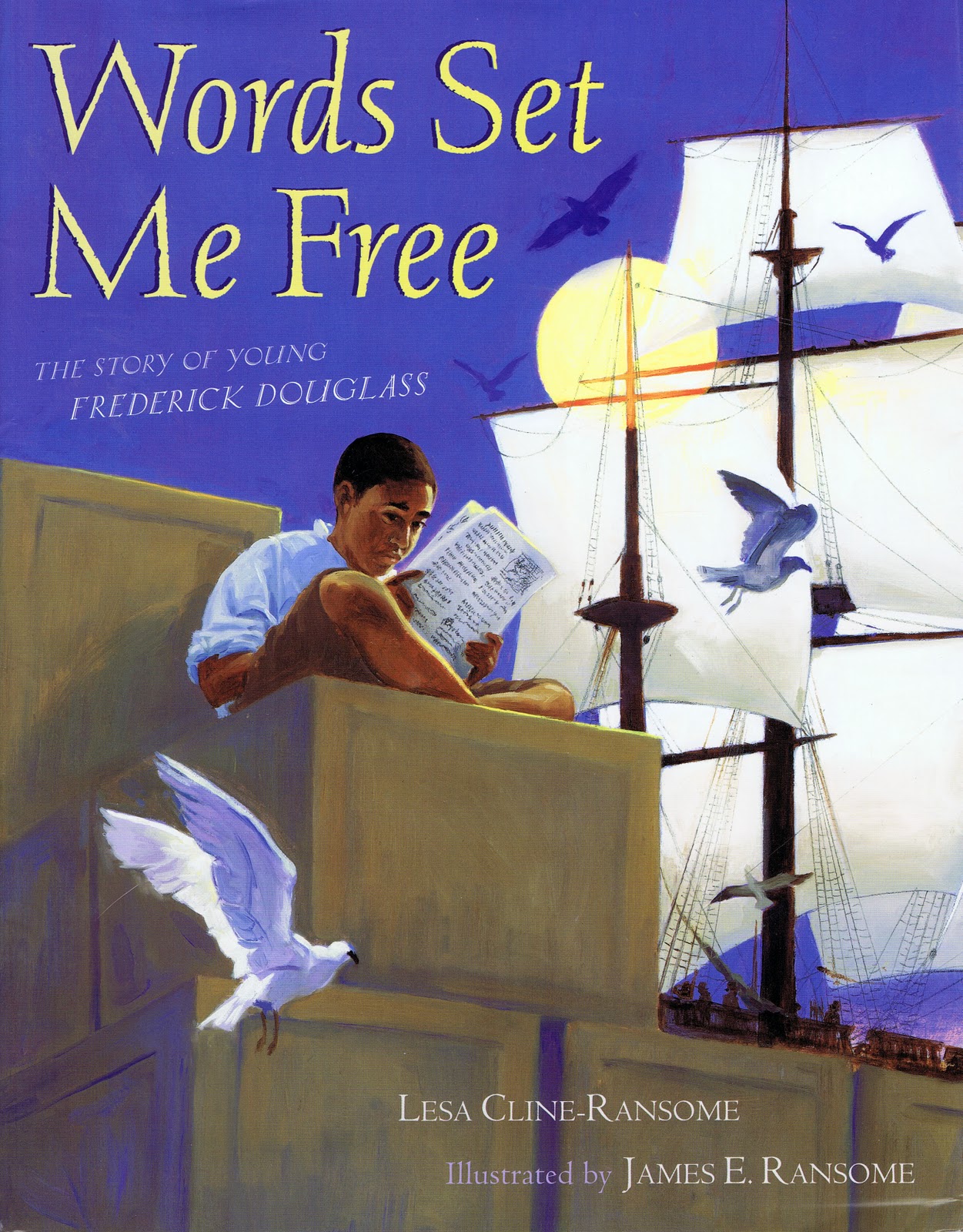

13 Feb / Words Set Me Free: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass by Lesa Cline-Ransome, illustrated by James E. Ransome

The award-winning wife-and-husband children’s book team of Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome capture Frederick Douglass’ early years from his slave birth to his first escape attempt as a teenager. Using Douglass’ autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, American Slave and pulling quotes directly from Douglass’ own memories, author Cline-Ransome presents the book in first person, immediately drawing in young readers to intimately share this story.

The award-winning wife-and-husband children’s book team of Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome capture Frederick Douglass’ early years from his slave birth to his first escape attempt as a teenager. Using Douglass’ autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, American Slave and pulling quotes directly from Douglass’ own memories, author Cline-Ransome presents the book in first person, immediately drawing in young readers to intimately share this story.

Illustrator Ransome deftly balances the tragedy (little boy Frederick in an oversized shirt grasping his grandmother’s hand, the youngest slave children eating at the trough “just like the animals in the barn,” Frederick cowering under the master’s looming angry shadow) with Frederick’s resilient hope (his straight-backed wonder as he looks out onto big city Baltimore even with his small hands bound behind his back, his attention at the Missus’ instruction sitting side-by-side in the library, his dirt-scratched letters in the secret “school among the trees”).

Before he became the legendary Frederick Douglass, young Frederick was a slave, the son of a slave woman named Harriet Bailey. “They say my master, Captain Aaron Anthony, was my daddy.” Raised by his grandmother, he only saw his mother in the middle of night when she managed to visit. Harriet Bailey’s arduous 12-mile trek to see her son is lovingly, achingly captured in last year’s Love Twelve Miles Long by Glenda Armand, which makes a fine companion title to Words.

Frederick spends his childhood being shuffled from master to master. At 6, he’s separated from his grandmother. At 8, he’s “rented out” to the mistress’ brother-in-law in Baltimore. His new Missus greets him with “the first friendly white face I had ever seen.” She teaches Frederick to read – illegal at the time – but her pride in his learning soon turns to shame when the master finds out: “‘If you teach him to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.'”

When Frederick is sent back to his birthplace plantation, he “was not the same [boy] who had left years earlier. That young boy was replaced with a fifteen-year-old who was free on the inside but not yet free on the outside.” With new knowledge and new friends, Frederick daringly attempts his escape: “I always knew that somehow words would set me free.”

Although the “Author’s Note” on the final page reveals the failure of Frederick’s first escape plan, Cline-Ransome also provides an achievement-filled overview of Frederick’s later life. As tragic as the circumstances were of his youth, Cline-Ransome highlights Frederick’s tenacious determination throughout her narrative, an inspiring reminder to her readers of his future accomplishments to come.

Readers: Children

Published: 2012