07 Mar / United States of Japan by Peter Tieryas + Author Interview [in Bookslut]

Alternate histories have been “a thing” for decades. Lauded titles are many, but World War II-related novels in which the so-called good guys don’t win seem to have yielded quite a few bestsellers through the decades, including The Plot Against America by Philip Roth, Fatherland by Robert Harris, and the cult Darkness series by Harry Turtledove. Philip K. Dick received the coveted Hugo Award in 1963 for The Man in High Castle, in which Japan and Germany rule over what was once the United States of America.

Alternate histories have been “a thing” for decades. Lauded titles are many, but World War II-related novels in which the so-called good guys don’t win seem to have yielded quite a few bestsellers through the decades, including The Plot Against America by Philip Roth, Fatherland by Robert Harris, and the cult Darkness series by Harry Turtledove. Philip K. Dick received the coveted Hugo Award in 1963 for The Man in High Castle, in which Japan and Germany rule over what was once the United States of America.

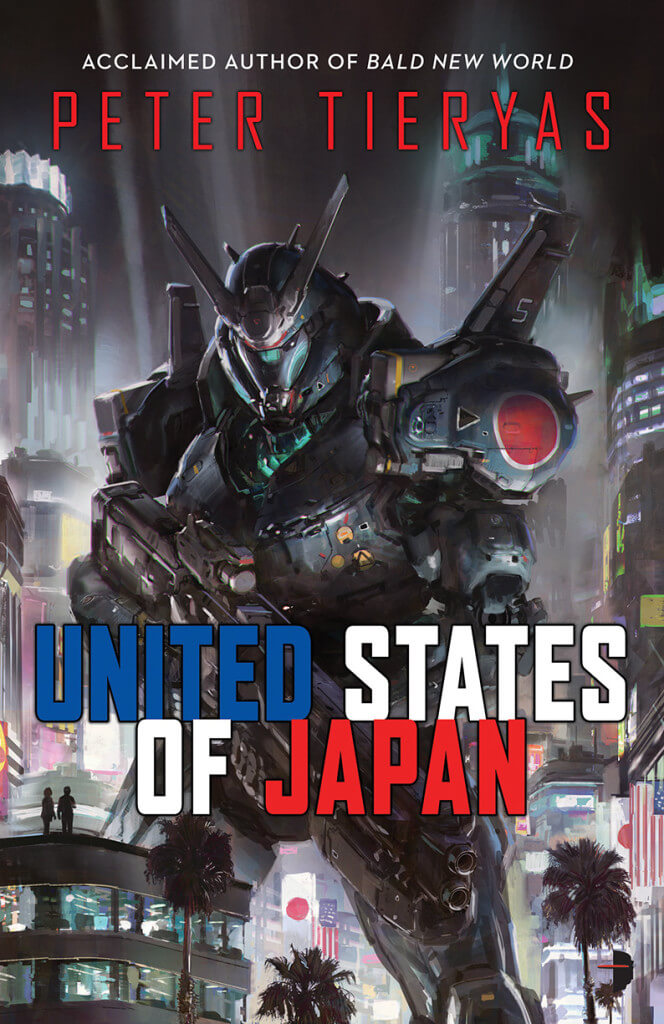

In what he calls a “spiritual sequel” to High Castle, Peter Tieryas is about to reveal his United States of Japan [USJ], which is scheduled to hit shelves this month. In Tieryas’s disturbing new world, the Japanese did not just invade Pearl Harbor but the mainland as well – and won. Starting with the release of imprisoned Japanese Americans from War Relocation Authority Centers, the Japanese victors take control of the western half of the continent. The Emperor is a god who cannot, will not, be disobeyed, and even a hint of questioning his power can provoke a quick death sentence.

In 1948, Japanese American Ruth Ishimura and half-Japanese, half-Chinese American Ezekiel Song are pregnant. With the end of the United States of America, Ruth and Ezekiel are finally free to leave their oppressive internment camp and eventually make their way to an unrecognizable, battered and bombed out Los Angeles. There they become a family of three with the birth of their son, Beniko Ishimura.

Four decades later, Captain Beniko has quite the reputation as a lothario and foodie. He nearly failed out of Berkeley Military Academy for Game Studies, and yet he’s proven he has unparalleled programming and decoding skills. He’s best known – lauded and feared, too – for turning in his own parents for betraying the omnipotent Emperor. He’s not sure he can trust his latest girlfriend. Although he didn’t get his expected promotion to major, he does receive a strange call from a powerful someone he hasn’t heard from in years – about arranging the funeral for a young woman he considered to be a little sister of sorts. And then Agent Akiko Tsukino shows up, initially tasked with solving a suicide, which leads – of course – to deeper and deeper layers involving serious threats to the USJ, centering around a new video game called the United States of America. A rebel group called the George Washingtons – complete with oversized white wigs – just might be plotting a new quest for freedom. Let the games play on!

With a professional background in gaming, films, and special effects – impressive credits include movies such as Men in Black 3 and Guardians of the Galaxy, with regular gigs for LucasArts, the gaming division of LucasFilm – Tieryas clearly draws on his cinematic expertise to create USJ. A heart-thumping, must-turn-the-pages, quick read, USJ is Tieryas’s third title. His Watering Heaven, a short story collection published in 2012, was a Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award long-lister. His 2014 debut novel, Bald New World – clearly a nod to a brave new world in which everyone everywhere loses all their hair – got him well-deserved attention when it appeared on Buzzfeed’s “15 Highly Anticipated Books of 2014” and Publishers Weekly‘s Best Summer Books in a starred review. Thanks to prepublication excitement that’s been building since last year, USJ arrives already included on numerous “most-anticipated” and “most-promising” lists.

Joining the many alternative history titles that have come before USJ, Tieryas – Korean-born, peripatetically raised throughout the US since he was a toddler, who now calls San Francisco home – is certainly one of the first Asian Pacific American writers to imagine a world with the so-called enemy as victor. Straightforward as that may sound, Tieryas has been remarkably careful to avoid oversimplifying issues, to eschew overtly demonizing one government over the other, to present his story in all the nuanced shades of grey. Readers, of course, will need to make their own decisions as to what side they fall on.

So did you ever worry about offending readers with USJ? That certain readers might bristle at the thought of giving power to “the enemy”?

All the time. I don’t want to offend or distract people from reading the book. At the same time, I try to write what I feel is true to my beliefs, or at least the value system the characters in the world follow. If I unintentionally offend by conveying a morality I personally disagree with but feel is appropriate to the characters (as in some of the imperial doctrine propagated throughout the book), I feel bad, but if I try to please everyone, I’ll just write the bland corporate-speak no one likes, and an unrealistic tale to boot. Finding that middle ground is always nice, but I push the envelope with my message and rely on my editor to tell me if I’ve gone too far.

A preview of USJ was published on Tor.com recently and someone asked if I felt the internment of Japanese Americans would justify America losing to the Japanese Empire. There’s no way I could ever feel that. But at the same time, I wanted to convey the complexity and the horrors of what [the character] Kujira describes as choosing between “the horrible and more horrible.” Under an authoritarian system – independent of ethnicity or race – how do you handle making such horrible choices? How does that shape and inform your whole value system? I incorporate racial dynamics, but do so in a way to reverse the “normal” expectation of the Asian being subjugated by the subjugator – is that what will challenge readers? If it were non-Asians in that subjugator role, would there be less, more, or equal offence? Those are all things I pondered and still don’t know for sure.

Let’s back up – what inspired you to write USJ?

I was working on a project with my friend James Chiang (called Dr. 2) and I had been studying the past of World War II, especially in Asia. I’ve always been surprised by the scarcity of material in the West from the Asian side (Korea, China, etc.). The more I read, the more I wondered why so little was known and I wanted to explore that. It was around that time I reread The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick and learned he wanted to write a sequel, but was too disturbed to go through with it. After Bald New World got some really nice reviews, it gave me the confidence to tackle these issues. It’s been an interesting challenge in that I don’t want to overly politicize or make the book didactic, because then it’s like getting a long, boring lecture. How to inform, while also entertaining readers and telling them a story with people you care about – ultimately, that’s the combination of factors that led me to pick USJ.

USJ clearly needed a lot of historical research to make it believable. How did you go about doing that?

By reading every book I could get hold of on the [Japanese] Empire, watching documentaries, talking to people in Asia, etc. One of the stories that didn’t make it in was how people in certain towns in China, specifically women, would put mud over their faces to mask who they were so soldiers wouldn’t kidnap them. A lot of stories like that informed the background. At the same time, I wanted to make sure the historical elements stayed in the background but were organically integrated in the backdrop, allowing readers to discover the world rather than being told such and such happened. The editing process was especially intense as I checked everything over with my editor, from the battles to the quotes. Wiki is nice, but can sometimes be wrong, so I made sure to double-check everything and not use Wiki as a last source unless there was just nothing else.

Creating unique other worlds must take a lot of organizational skills. You have to figure out the endless details of what’s real in that world. How do you keep track? Do you have outlines of your alternate worlds?

USJ began as a novella and I originally wanted it to be a shorter work, which is ironic in that it’s my longest book of three. So in that sense, at first, it was just a bunch of notebook scribblings. As the book went on, the outlines got bigger and bigger, drawing charts, maps, etc. So, yes, outlines and lots of notes.

USJ is also your third title in which you’ve managed to avoid reality, so to speak. What’s your fascination/dedication to alternate worlds, dystopia, sci-fi?

Oh, that’s a great question! One thing I do want to note is that I have been a little disturbed by how dark USJ is – at least the research. I think my fascination has to do with me wanting to be able to tell a story from a different perspective. In USJ, that the Empire is the predominant force and that Americans get discriminated puts racial tensions in a different light, which is different from me lecturing someone for being racist – which usually would only arouse hostility. Being forced to change perspectives is why I love sci-fi like Star Trek, Planet of the Apes, etc. so much.

USJ is not so much about the Japanese Empire as it is the contemporary world. Almost every issue finds reflection in current events and some of Akiko’s weird daydreams/subconscious meanderings are references to events happening now. Let me clarify, though, that while I want to bring to light many of the tragedies from WWII, I also want to use that past to inform and explore history’s relationship to the present which is one of the reasons I had it take place in the late ’80s rather than the ’60s like High Castle.

You mention your personal interest in Japanese culture in your acknowledgements – what’s the story there? What sparked your initial curiosity?

I’ve always loved Japanese culture from books, games, and films. Videogames, obviously, are huge, as I’ve been playing them since they came out. Films by Akira Kurosawa and Fukusaku are big inspirations and I constantly draw on them (there is even a nod to actor Toshiro Mifune in the book). I love the ideas they espouse, especially about honor, integrity, and sacrifice, but also, the flaws that give them a relatable humanity. That’s part of what bothers me about the perceptions of Asia that focus on servility, the exotic, blah blah, and silly stuff like that. What about the bravery, ingenuity, creativity, and even imagination (not just in math and engineering, either)?

Speaking of imagination, your career has been quite eclectic in the various kinds of media in which you’ve worked – film, animation, gaming, digital, etc. Where does the writing come in? And how did you become a writer?

Ever since I was a kid, all I did was write. I would play games and write about them. Same with films. Writing sort of fired up my imagination and I just loved telling stories about my friends and those around me. In cases where there was any suffering to be had, I would first write about it and try to come up with solutions so I could act on them. I don’t want to use writing as a substitution for life, but a contemplation, impetus, and reflection – though I do occasionally vent!

In addition to your own writing, you’ve also worked closely with other people’s writing via Entropy magazine, where you’re listed as a cofounder. Tell us a bit about this “community of contributors that publishes diverse literary and non-literary content.” And are you still involved?

I’m only involved as an outside editor right now. I had to step down as co-chief editor because there were movie reviews on the site and it could cause a conflict of interest. I still contribute interviews and whatnot, but for the time being, more as an external editor occasionally contributing.

As for the community, we really wanted to find a place for new voices. In a lot of magazines, you see the same writers over and over. And that’s fantastic. We just wanted to create a space not only for different writers, but different kinds of stories, so you’ll see articles about literature, as well as video games and food.

Think you’ll ever write a book that happens – for lack of a better phrase – in the real world?

I would love to. I think many of my short stories are in the real world, and, while some have speculative elements, most are more reality-based. I think it’ll just depend on what moves me at the time.

Since we’re talking reality, I noticed that the names on your three book covers differ slightly. The first two have “Peter Tieryas Liu,” but this latest stops at Tieryas. Is Liu your Korean surname?

I was born in Korea. My [legal] family name is Tieryas. Liu was a pen name I used because I was working and just wanted to have a separation between work and writing. The name was inspired by one of my favorite characters in Chinese literature, Liu Bei [second-century emperor of the Shu Han state during China’s Three Kingdoms period, made gloriously popular in the historical novel, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, considered one of the four great classical Chinese novels ever].

I delve into [the legal name change] in Bald New World, but a big part of me wanting change was because I knew I wanted to start anew. I picked Tieryas because it was a mix of two Asian words and a parable I liked related to Liu Bei.

So what two Asian words make up Tieryas?

It’s from tian (天, heaven) in Mandarin and ryu (竜, dragon) in Japanese, and is related to that story in Three Kingdoms about how everyone is a dragon underwater waiting for their time to rise. Some become too bitter from suffering and become sea serpents, others die before they rise up. Also, I pronounce Tieryas “to-rise,” or “to-rye-us.”

And what’s the fascination with Liu Bei?

I liked Liu Bei because among all the characters in Three Kingdoms, he’s not a great fighter, not a super intelligent tactician, but just a very cool person who is thoughtful and caring of those around him. He is very humble, yet tries hard, and cares for his people. Also, because I came from a poor background, I related to the idea of this guy who also comes from very humble beginnings. Of course, he’s royalty, which is a big difference. Three Kingdoms includes many moments and decisions of his that I am particularly moved by, and I loved his concern for people, for deeper issues, which is what I aim for in all my writing.

So your latest writing has definitely been generating serious buzz. Barnes & Noble named USJ one of the “42 SF/F Books We Can’t Wait to Read in 2016” and Publishers Weekly included it in their “Spring 2016 Announcements: SF, Fantasy & Horror: Worlds Turned Upside Down” must-read list. Even Popular Mechanics announced USJ as one of “16 Sci-Fi Things To Look Forward To in 2016.” How’s all that fabulous anticipation treating you?

The announcements are great and mind-blowing. At the same time, because a lot of the attention for USJ is on the mecha [a sci-fi genre involving robots and/or human-controlled machines] aspect, and not necessarily the social issues, I’m curious how people will react when they find out mechas are part of the background and not the focus – I don’t want readers to be too shocked. Early reviews have trickled in, and almost every single one of them mentions surprise that it isn’t just mecha escapism (in a good way). I forgot who said it – there’s a line that if you take people’s praise or buzz seriously, does that also mean the same for the inverse? I’m grateful for the publicity, but I just try to focus on the book itself.

Your Wikipedia page – because you have one – lists your “Literary Influences.” Quite a collection: “Tieryas has cited Philip K. Dick, Franz Kafka, Herman Melville, Alan Moore, Friedrich Nietzsche, George Orwell, Pu Songling, John Steinbeck, Cao Xueqin, and the Biblical Book of Ecclesiastes as literary influences.” Those all true? Any particular standouts you’d like to highlight further and why? And what’s with the Book of Ecclesiastes?

Ecclesiastes! That book seems such a strange fit with the Bible. Reflections on the futility of life. A poetic contemplation that says don’t be too good or too evil. I always remember it in the sense that it reminds me to keep a perspective on life as the author (Solomon, according to tradition, but that’s debated) who had everything, but claims it’s all vanity, a chasing after the wind.

I also want to point out Orwell. I had this strange fascination after reading 1984 to want to know more about the thought police. Like who in the world were they? How did someone become one? What went on behind the scenes? Some of those thoughts crept into the scenes with Akiko and the Tokko [secret police]. Also, Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony” was a direct inspiration for the commandant in Catalina.

That sure is a list of many, many men! What about women?

That’s a great question and it’s not much of a defense, but I didn’t actually write the Wikipedia entry. If the question had come up, as in a few other recent interviews I’ve done, I would also – of course – include quite a few women, including Pearl S. Buck (her writing is gorgeous and, even aside from The Good Earth, she has so many great books, including sequels to Good Earth), Kameron Hurley (her recent Worldbreaker Saga was one of the most powerful and visceral works I’ve ever read), Sylvia Plath (I go back to The Bell Jar every few years), Aliette de Bodard (I just wrote in a short review of her work that her writing is so good, it’s almost like “a poetry of destruction”), Roxane Gay (is there any praise about her that hasn’t already been said? – she’s amazing), Octavia Butler (Lilith’s Brood was brilliant and I recently included her book in a list of titles I thought would be awesome as videogames), Maxine Hong Kingston (from my time at UC Berkeley where she was a professor and the memory of reading her powerful The Woman Warrior), and a personal favorite, Margaret Weis. I used to take [Weis’s] books (Dragonlance, Deathgate Cycle, etc.) to class in high school, hide them behind my textbook, and read them. [I had the] great honor to meet her at a writing conference where she had so many encouraging words for my writing at a time I was feeling pretty down about my work. I still remember a banquet at that conference, during which all the guest speaking writers had a special table. Margaret actually sat next to me and when the conference director asked if she’d like to move to the main table, she politely declined and stayed at my table. That was one of the most special moments of my writing career.

Also, for Entropy where I now guest edit, I’ve started an interview series with women writers whose works I really admire. My first two [interviews featured] Sueyeun Juliette Lee and Michelle Bailat-Jones, both of whom are fantastic. I hope to get back to the series when things get a little less hectic with USJ.

Since we’re talking God (at least on the page via human interpretation), dare I ask – what’s your religious background? How did that come into play in USJ?

Oh yeah, I love talking religion because it’s so much more complex. I think Tupac put it something like, God isn’t just a policeman waiting to bust you up for breaking rules. Books like the Bible and other religious texts are people’s way of understanding the universe. As our tools and technology increase, we use different tools, but the pursuit is ultimately the same. There are many ideals in Christianity that I greatly admire: love, the idea of sacrificing worldly desires in pursuit of ideals like selflessness, etc. The same ideals apply for many of the religions out there.

In USJ, I refer to religion a lot to show how horrible circumstances change the face of religion, making believers much more extremist. They’ve modified their religion to fit the new paradigm. I don’t like it when people consider any religious text a science book. I, like many others, spend a lot of time wondering about the nature of the universe. I think what we call “God” is in essence the universe in a different name, and we’re all trying to learn its rules, whether through religious codices or mathematical formulas. Of course, it gets scary when people misuse that.

In light of misuse, religion always provides ample opportunities to offend, regardless of intentions. Back to that fear of offending: are you just a subversive sort of person?

One thing that strikes me about Buddha, Jesus, and every major religious leader, is that their followers always ask them questions. And they’re never told, “Don’t question, just have blind faith!” No – questions are actually encouraged and everything is meant to be challenged. Jesus challenges the whole status quo, was the ultimate subversive, and he was killed for it. If a person can’t have their faith challenged without it shattering, then – well I’m becoming offensive again, no?

As for future projects – what’s next for you?

I’m hoping to take a long break. Depending on how USJ does, it’ll determine my future plans. There are some things with Angry Robot in the pipeline but if I mentioned anything now, they’d probably absorb me into the Borg Collective and make sure all I spout are subversive platitudes to make everyone perpetually happy.

Author interview: Feature: “An Interview with Peter Tieryas,” Bookslut.com, March/April 2016

Readers: Adult

Published: 2016