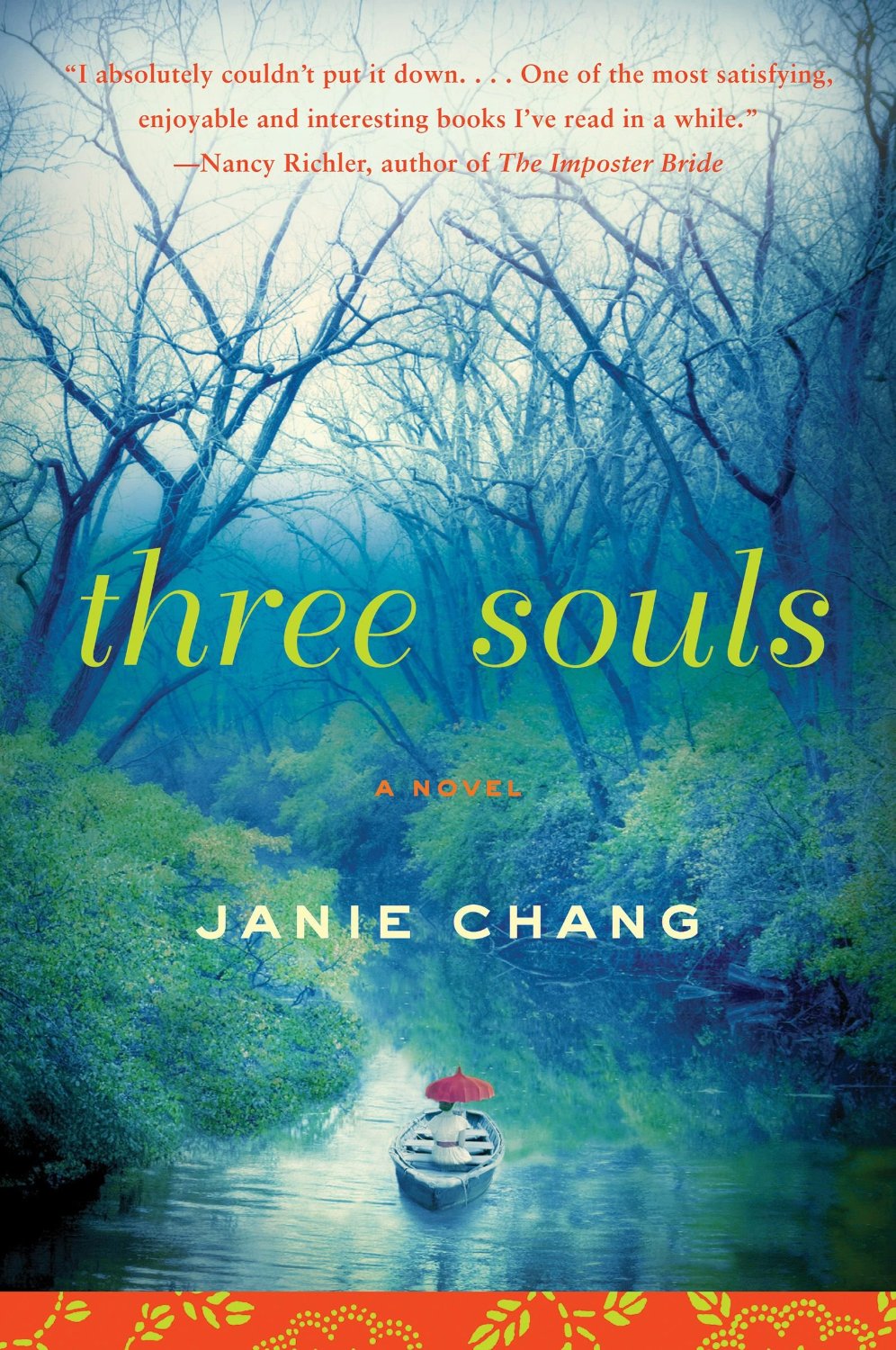

04 May / Three Souls by Janie Chang + Author Interview [in Bookslut]

“We have three souls, or so I’d been told. But only in death could I confirm this.” Thus begins Canadian author Janie Chang’s debut novel, Three Souls, in which a dead woman will learn about a life that ended too quickly, and how she might still affect the lives of those left behind.

“We have three souls, or so I’d been told. But only in death could I confirm this.” Thus begins Canadian author Janie Chang’s debut novel, Three Souls, in which a dead woman will learn about a life that ended too quickly, and how she might still affect the lives of those left behind.

Song Leiyin settles into the rafters of a small temple, overlooking her own funeral ceremonies, unable to go any farther. “I have knowledge, but no memory,” she realizes. She knows she is no longer alive in the “real world,” but neither has she made the expected journey to the afterlife. To do so, she will need to rely on her three souls – the delicate yin, the impatient yang, the watchful hun – to lead the way. “You must understand the damage you did,” her souls admonish and warn her. “Then you must make amends to balance the ledger. Only then can we ascend together to the true afterlife.”

Seven years ago, in 1928, Leiyin “stepped off the path that had been paved for [her]” and changed not only her intended future, but that of many others around her. The youngest child of a wealthy, educated, comparatively nontraditional family in a China on the cusp of revolutionary change, Leiyin wants nothing more than to continue her learning. For modern readers, her goal is laudable: “I had to do my part to bring our young nation into the twentieth century.[…] Nanmei [her best friend] and I had been determined to become teachers.” But for Leiyin’s father, in spite of all his learned ways, further education for his daughter is deemed irrelevant, setting in motion the events that will lead to Leiyin’s early demise. Before she succumbs, she will fall in love, attempt to steal her independence, be banished to a remote town as the bride of a man she does not love, and be forced to live a constricted life she never imagined. Until it’s over. And still, Leiyin must go on.

The Taiwanese-born, ancestrally Chinese, globally raised, Vancouver-domiciled Chang spent her entire childhood with these stories, inheriting from her parents the tales of generations that came before. She remained the family repository until last spring, when she presented the world an epic, sprawling novel in which family tales and legends had been reformed and remade into almost 500 pages permeated with love and longing, independence and entrapment, regrets and hopes, revolution and pettiness, promises and betrayal, and more.

So I must start with the obvious: How did Three Souls come to be? You come from a family of storytellers – and I understand many of their stories are woven into your novel, especially your grandmother’s.

My grandmother’s story has haunted me all my life. My father used to tell me tales about his childhood and our ancestors. There seemed to be quite a few about unfortunate women, but out of all of them, his memories of his mother haunted – that word again – me the most. It was so sad that she was educated just enough to understand what a career and independence could mean. She rebelled once, and was punished for it in a way that sealed her fate. It just seemed such a waste of intelligence.

There are other family anecdotes woven into Three Souls. The wealthy bride who brought a dowry that should’ve supported three generations was my father’s grandmother, and as in the book, it really was her husband who squandered it all in a single generation. The artificial mountain which Leiyin and her family climbed up for a picnic was real – my seven-times great-grandfather built it. It was demolished in the ’50s, I’m told, because it was unstable and no longer safe to climb. And of course, Hanchin was modelled in a small way after Qu Qiubai, the revolutionary writer who was an early mentor to Mao and who was executed by the Nationalists when he was only 35. He was my grandmother’s first cousin.

Speaking of that “waste of intelligence”: Your choice to make your protagonist Leiyin a ghost – how much of that decision has to do with the “invisibility” of women in traditional societies? Leiyin herself comes from a highly nontraditional (at the time) family – was that at least a partial reason as to why she couldn’t survive longer than she does?

I’m so glad you picked up on that. Yes, it felt very apt that Leiyin developed into a ghost because, like the women of her generation and generations before, she could not influence events or decisions directly; she had to work behind the scenes. She was born into a time of transition.

How did you do your research for parts of the narrative that didn’t have family history?

I was lucky in that, having grown up with these stories and with parents who were of that era, I had a good sense of what it was like to live in a small town in China, to belong to a family of good background sinking into poverty, what people believed and found acceptable. So for a lot of the research, it was for the sake of validation: to make sure that what my father told me, and my impressions, were common truths rather than one person’s memories.

I had to make sure dates and events were in synch with the storyline – there was so much going on in China during those years, you have to be careful about the sequence of events.

One funny thing about validation – we have a friend of the family who is perhaps a half-generation older than I am. She’s a Chinese literature major and very knowledgeable, so I figured if my story passed her filters, it would be accurate enough for all but the most scholarly of historians! She told me there were two things that didn’t ring true. I fixed the first one, but the other was that in those days, it was simply impossible for large clans of status (in Chinese, it’s da jia ting, meaning “big family” or “important family”) to arrange marriages in just two weeks. So this friend found the turning point of Leiyin’s life hard to believe. And yet that was exactly how my grandmother’s marriage was arranged – in two short weeks, propelled by her father’s anger. The circumstances were so unusual the story passed into family legend.

You grew up with these stories most of your life. How long did it take you to put them on the page? And how long before the book hit shelves?

Okay, but before I answer that, here’s something I really urge readers to do if they have any interest whatsoever in family history. Memory is ephemeral. Get people to record what they remember. More than 20 years ago, I asked my father to record our family stories and his memories on tape. I’m so glad I did. Try and preserve your family’s heritage because, believe me, when those sources are gone, they’re gone, and all you have left are regrets that you didn’t spend more time with your elders.

About 15 years ago, I wrote down all the stories I could remember my father telling me. The motivation was that my nephews and nieces never had the opportunity to hear their grandfather tell these tales. I published them using Blurb as gifts for my family. Now you can find them on my website.

Then my father died and my mother went into care because she was suffering from dementia. That really makes you think about making time for your dreams. I didn’t want to end up sitting in a rocking chair when it’s too late, saying to myself, “Should’ve tried harder.”

That’s when I went into overdrive. I took a one-year creative writing program from Simon Fraser University and worked on a draft manuscript during that year; I wrote every night for two to three hours, six nights a week. That was in 2011. I revised. I edited. I found an agent in 2012. I sent the manuscript to a professional editor for a final run-through. My agent went off to pitch. HarperCollins Canada bought the book, and it was published in Canada in August 2013 and the U.S. (William Morrow/HarperCollins) in February 2014.

I should mention that making the time for the novel was a family decision. My husband made dinner every night so that I could write.

And you seem to have had a comparatively easy transition into becoming a published novelist!

I don’t know about “easy” so much as “accelerated.” In the computing world, there’s the notion of elapsed time versus actual processing time. You could say I put in a lot of dedicated processing time. And remember that many elements of the novel had been in my head for years. It was a matter of getting them down on paper, shaping the story, and developing the characters. The most important first step to getting published is FINISH THE DAMN BOOK.

I must also say that it made a big difference to have taken a creative writing program that pulled together everything in a way that made sense to me. It covered both the craft and the business of writing. I knew getting to publication would be a lot of work. I had no illusions about how high the bar is these days, and even then, you have to get lucky.

You mentioned your scholarly friend’s feedback above. How did your storytelling family react to the book’s publication? Have any of your Chinese/Taiwanese relatives read it? Can you imagine what your grandmother might have said?

My brothers and their families are really proud! My father passed away in 2000 and my mother is not capable of reading more than a paragraph at a time now or retaining any of it. That’s why the book`s dedicated to her, so that if nothing else, she knows I wrote a book for her. All my relatives who can read English have read it. My grandmother came from a family that valued the literary arts, so I like to think she’d be pleased that a granddaughter has carried on the family tradition.

Do you believe in ghosts? Any hauntings – that word again! – that you want to share?

What can you say when you come from a family with a legacy of ghost stories? I mean, when I listened to my father tell the tales, it was obvious that generations of our family believed absolutely in those stories. Maybe he didn’t, but he told them as if they were real, so they were very real to me!

No, I don`t actually believe in ghosts. I do believe there are phenomena we can’t measure or perceive. People in medieval times couldn’t see bacteria and microbes, but they’re there.

Although, I’m fairly sure I saw the Goddess of Mercy once, when I was a little girl in Taipei. It was very early in the morning and no one else was up. I was staring up at the clouds. She was in the clouds, a white figure superimposed against the sky, turning her head slowly from side to side, looking down on the city, moving very slowly and majestically across the horizon. She looked just like the paintings of Chinese immortals.

A year has already flown by since Three Souls pubbed last spring. What’s the best thing that’s happened? What’s the most disappointing?

I think the best thing was attending literary festivals and meeting authors I had admired for so long. It was like a fairy tale because then every so often I’d realize, “OMG and I’m an author too!” People related to me as an author, not as a high-tech professional. It was as though I’d taken on a totally new persona!

The most disappointing … hmm. You know, just getting published was beyond my expectations. To have a second novel under contract is beyond my expectations. To have an agent from the literary agency that was my top choice is beyond my expectations. I know what the odds are. So I’m having a hard time picking out a real disappointment.

Perhaps it`s been the difficulty of adjusting to a life of writing. I have nearly zero social life when I’m working on a book and it’s been hard on family and relationships. You hope you can keep it all in balance, but as an author friend said, “It’s not easy being friends with an author. We’re hardly ever around and when we are, we’re living in our heads.”

You’ve got more OMG ahead: Let’s talk about Three Souls going celluloid – you write in your blog about a “Bollywood + Chinese martial arts fusion treatment of the novel.” Possible? Sounds perfect!

Can we not talk about the film option in quite such exuberant words? The challenges of getting a film made are so enormous. As my agent says, just enjoy the compliment and get on with your next novel. She’s a great career coach. But yes, I do daydream sometimes about actually going into production and, for some reason, a Bollywood treatment keeps popping up.

Okay, we’ll get “exuberant” about something else you’ve been directing great efforts toward: Authors for Indies, a national initiative, which will launch the weekend before this interview pubs. Do please tell us more. How did it evolve? What’s so special about May 2?

As mentioned earlier, I attended The Writers’ Studio at Simon Fraser University in 2011. One of the things then-program director, Betsy Warland, advocated was supporting the writing community. Writing is a very solitary pursuit; for our own sanity and to support others, we need to get involved in the writing community.

Once you start learning more about the business of writing, you can’t help but become aware of the plight of independent bookstores. These are the bookstores willing to take the risk of putting new and local authors on their shelves, the ones who promote a book because they love it, not just because it’s on a bestseller list.

Then I read about Indies First, the initiative started in 2013 by Sherman Alexie, and I thought, “Well, how hard could this be to organize in Canada?” And with those words, I was doomed to take action.

May 2 is a day when authors across Canada volunteer as guest booksellers at independent bookstores. More than 100 stores and 500+ authors have signed up. The goals are to bring lots of traffic into stores on May 2 so that people in the community get to know their indie bookstores, and to raise awareness of how important they are to our communities. The website features blogs written exclusively for [Authors for Indies] by diverse and eminent Canadian writers, and lists the participating stores by province and the authors they are hosting.

It’s been a ton of work, with a very small team of volunteers, and I’m thrilled with the results so far. My personal highlight was when [award-winning Canadian historical fantasy writer] Guy Gavriel Kay emailed and asked, “My son is a filmmaker, would you like a video?”

We’ll be looking for the recaps on the website! And what’s next after the May 2 launch?

After May 2, I’d like to get some feedback from the bookstores [about whether] it was a worthwhile effort for them – because it’s a lot of work on their end just to organize all the authors and events in each store. If it’s worth it, I hope Authors for Indies can become an annual event, with more volunteers and more budget.

The month of May, in the U.S. anyway, is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, so I’m feeling compelled to talk about race/ethnicity here: Whenever a writer of Asian descent debuts a novel, comparisons to Amy Tan seem inevitable – especially for women APA writers. I assume that happened to you at some point. This seems downright ridiculous, especially since the realm of APA literature has grown exponentially over the decades — in numbers as well as quality of content.

You know, for a start I’d like to just get past the female author thing: “Why isn’t your female protagonist more likable?” I’ve heard repeatedly. But no one ever worries about whether male protagonists are likable, they become “anti-heroes.” Grrr.

As you say, the comparisons to Amy Tan and also Lisa See are inevitable. Amy is a trailblazer and Lisa is a wonderful storyteller; both are so well respected. If those are the benchmarks, I’m fine with it. Honestly. In fact, [I take it as] a compliment; when this comes up, it’s never been a comparison made in a bad way.

Amy Tan was definitely a publishing pioneer – she also had the marketing genius and unbelievably lucky timing of überagent Sandra Djikstra behind her. But she’s also been highly criticized for pandering exotica for mainstream audiences. Lisa See fares a bit better. As part of the Djikstra stable, do you ever worry about that sort of reaction?

Short answer no. Longer answer – you can’t write to please everyone. I think we write the stories we need to tell, in a way that we can bear. For example there are experiences about being a Chinese daughter and an immigrant that have been negative, humiliating, and infuriating, but I don’t know whether I’ll ever be ready to share them. Contrast that with Jean Kwok’s Girl in Translation – that took tremendous personal courage to write.

In this regard, it must be tough being Amy Tan. It’s like she’s been set up as the spokesperson for all things literary, female, and Chinese. She is so visible [that] the mantle gets thrust upon her all the time, while lesser-known authors can write “mainstream,” or Asian-themed historical novels, or sci-fi/fantasy. We can be storytellers first and foremost without attracting that sort of criticism. Why should female Asian authors be required to provide serious social commentary all the time? The ultimate goal is for writers of every ethnicity to flourish in every genre. [… click here for more]

Author interview: Feature: “An Interview with Janie Chang,” Bookslut.com, May 2015

May 4, 2015 update from Janie Chang: And as for Authors for Indies, which took place over the weekend, we will have national sales figures by Wednesday/Thursday from BookNet Canada.

The #Authors4Indies would’ve been top trending topic in Canada on Saturday if not for that royal baby. CBC Books offered us a Twitter takeover, and we have two authors doing two shifts for the takeover (east coast & west coast).

We ended up with 692 authors, 123 bookstores, and coverage in the Big Three Canadian newspapers – Globe & Mail, Toronto Star, National Post.

I’m kind of exhausted, and now, back to novel #2.

Readers: Adult

Published: 2014