31 Jul / Talking with: Edward Gauvin … in full [in The Booklist Reader]

A truncated version (edited for printing space) of this interview was published in the July 2019 issue of Booklist. The full interview appears below.

A truncated version (edited for printing space) of this interview was published in the July 2019 issue of Booklist. The full interview appears below.

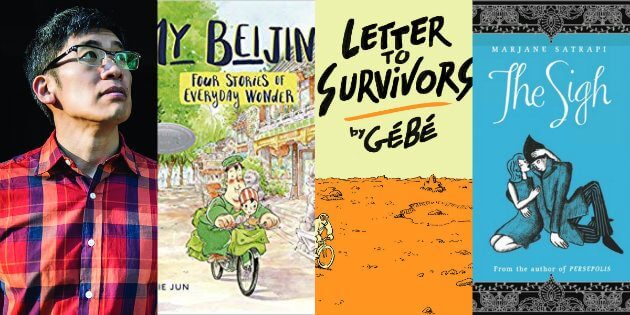

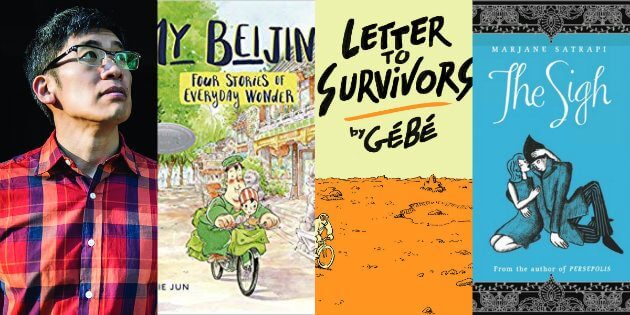

With over 300 publishing credits, Edward Gauvin might be the hardest-working French-to-English translator ever. That tenacity has earned him major awards, including the John Dryden Translation Prize (twice), and lauded NEA, PEN America, and Fulbright fellowships. His nimble skills have provided substantial attention to French graphic novels, including starred Booklist titles such as Gébé’s Letter to Survivors, Nie Jun’s My Beijing (one of this year’s Top 10 Graphic Novels for Youth), and Marjane Satrapi’s The Sigh.

Beyond linguistic ciphering, Gauvin doubles as a writer. We’re outing him here: he publishes as H. V. Chao, with story credits in such venerable publications as the Saturday Evening Post and the Kenyon Review. His moniker, he explains, is “in honor of my mother, who raised my brother and me. She grew up in Taiwan, where her family fled in 1949.” As he carries on his dual literary life, appreciative readers can look forward to seeing his name(s) on many more future covers.

What were the major life turns that led you to becoming a French-to-English translator?

By dint of having to origin story in some form or another over the years, I keep trying to distill this to some not-quite-haiku reply, like the first page of Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman: Liberal Arts: Year abroad. Dumb luck. Decent taste.

Professionally, the landmarks are really Persepolis (translated by Helge Dascher, Anjali Singh, and Kim Thompson), for turning heads and making editors eager [for] French comics for the first time since Heavy Metal [a science fiction and fantasy comics magazine licensed from the French science-fantasy magazine Métal Hurlant]. Words Without Borders for taking everything publishers wouldn’t (sometimes later leading to publication). The NEA, for swooping in and saving me from two lean years after the mid-aughts comics bubble burst. That same year, I also lucked into a Fulbright to investigate supernatural fiction in Brussels. All along the way, editors, lit mags, and small presses made continuing the journey possible.

You couldn’t be more prodigious, with 300-plus translations! How do you pick your projects?

I’ve never really picked my comics work. In the sense that I say yes or no, sure, but not in the sense that I bring projects to publishers. Half my prose translations were my pitches; three of the 300-odd comics were ones I successfully pitched – which is not to say I never pitch or have given up, I just find it a very difficult proposition.

Short fiction is one area where I do get to do almost exactly what I want; the trade-off is that I do it on spec and then make the submissions rounds.

Count is tricky, and I keep it only roughly; plus, I’m counting in French editions, individual books never less than 48 pages, but sometimes several times that. Anglophone publishers may wait till a trilogy or series finishes in France, then release all the volumes in a single book in English, so my English count will be lower.

My comics work has really ramped up in the last four years, mostly due to major mainstream French comics publishers – Delcourt-Soleil, Mediatoon (Dupuis, Dargaud, and Le Lombard), and to a far lesser degree, Glénat – securing EU funding to commission translations directly, which are then released only in digital form, thus bypassing U.S. and UK publishers. Despite these being available from the usual services (Comixology, iBooks, Google Play, etc.), I’m not convinced readers know they exist. And though print rights to most of these books remain available to interested publishers, I’m not sure if their digital existence deters interest. But the initiative has allowed these French publishers far more freedom in the choice of material to bring into English as they raid their vast catalogs. Mediatoon’s editorial priorities, for instance, have really ranged all across the board just in the four years I’ve been working with them: from classics like Les Frustrés by Claire Brétécher (who Roland Barthes called 1975’s “sociologist of the year”); to long-running, reliably selling pulpy-soapy series; to the latest from name creators, plus some fun kids’ stuff.

You translate across genres, from nonfiction essays to prose fiction – but specialize in graphic titles. Does your approach change between genres?

I used to find creative work easier to translate because I felt taken in hand by the author, their world and idiolect; every work teaches you to read it, they say. Whereas nonfiction points necessarily to a world outside of itself; research is explaining that world to yourself in ways the piece may not have to. Since then, though, I’ve done enough biographical, historical, or nonfiction work, and mostly in comics, that the felt distinction has largely faded.

Working in comics has allowed me to translate across more genres – westerns, epic fantasy, science fiction, biography, reportage, memoir, chick lit, children’s, war, noir – than I might have encountered in prose, simply because the range of French prose we get here is narrower and, to my mind at least, more closely tied to national reputation or stereotype. (French import staples include gastronomy and high theory.) Genre is a deliberate game of ringing limited changes within a formula, and this is as true of style and language as it is of plot. Each work enters into an ongoing conversation with past but also international works. To some extent, it’s like genre speaks through me. The choice usually given translators of bringing the reader closer to the work or the work closer to the reader, in which the latter is often looked down on, is a false one in this case: reader expectations are part of genre, and reception an issue often overlooked in translation in favor of authorial intent or language.

Do you have a favorite genre? Favorite authors?

If by genre you mean novel versus poem versus plays, then no. If you’re talking genre like noir or romance, then well . . . I grew up on westerns and musicals. (There are some fine western comics, but I’ve yet to see a comics musical.) More recently, I prefer weird fiction and stories of the supernatural.

In general, I like works, not authors. But I’m a bad person to ask about favorites. I am, as the Paris ’68 protesters said of themselves, a Marxist of the Groucho school. Part of not caring to belong to any club that would have me as a member means I can see clear around anything I love to why someone else would hate it, which often leaves me feeling like a fan in bad faith.

That said, a graphic novel I enjoyed greatly and got to translate recently was Last of the Atlases by Fabien Vehlmann and Gwen de Bonneval, with art by Hervé Tanquerelle and Frédéric Blanchard. It’s an alternate history that introduces us to an Algeria where the War of Independence took place 15 years later because after WWII, the French were able to greatly modernize Algeria using nuclear-powered Iron Giant-style robots named Atlases. After a horrible catastrophe, the Atlas program is scrapped, and in the book’s present day, a small-time gangster is trying to rescue the last remaining Atlas from an Indian ship-breaking yard to fend off what he’s convinced will be an alien invasion. Vehlmann and de Bonneval are a pairing I’ve long admired, and their contemplative far-future tale, Last Days of An Immortal, [is] one of the few comics I ever successfully pitched and, like some of the favorite translations I’ve done, already out of print.

What are a couple of your biggest surprises as a translator? Any disappointments?

There’s the disappointment that some of the favorites among the books I’ve worked on are already out of print. There’s the fact that some highly esteemed publishers still feel perfectly fine today offering translators a page rate that’s less than half of what I started out at in 2006, and unashamed to use the language of love to guilt them into rates that, living wage aside, are just flat-out unfair to and unreflective of the labor involved. And it’s criminal that the going industry-wide page rate for basic lettering – not hand-lettering, mind you, or placing sound effects, but just balloon-filling, a job often done by interns – is twice that of translation. If translators are already traditionally “invisible” in prose fields, how much more so are they (or anyone who does text-based work, like letterers) in a medium where art has the upper hand? An industry eternally plagued by understaffing, shoestring budgets, and tight turnarounds?

What this points to is a fundamental misperception of what it is translation entails, because it is easily both a) more creative and b) less mechanical than basic lettering. Whereas “mechanical” and “rote” are both qualities popularly attributed to translating: it’s an activity for the machines. (Hell, Google’ll do it for ya. Except that Google Translate, like Soylent Green (and unlike most translation programs before it), is people. The work of human translators: crawled, combed through, and presented uncredited).

As for surprises: the richness and reward of the work itself, the very process of weighing words so closely, in so many different ways. Previously, people wandered into translation thinking it was something they could do, only belatedly to find its complexities fascinat[ing], and [learn it] might take a lifetime to fail to master. I’m on the tail end of that generation. I thought I knew what I was getting into, only later to realize that was ignorance, while people who choose translation now often do so with aspirational reverence for the act and academic acquaintance with its potential pitfalls and issues. Both go on to learn only through doing, but today’s grads, edgily hustling for publication or a paying career, would say it was their predecessors’ luxury to be able to learn in print.

It also surprises me how little many authors care to be involved in the translation process, when I’d thought all they’d want to do was talk about their own work. But this has largely spared me the kind of disappointments that plague translator conversations, about tyrannical or meddling authors.

With languages never staying static, are “timeless” translations possible? Do you adhere to any personal rules in your translations to ensure as-timeless-as-possible results?

The adage is that translations date faster than originals, but the dirty secret is, originals totally date. When they do, we add back matter and call it a scholarly edition: footnotes for references and language, reviews of the era for context. Updating the language of Shakespeare is a classroom staple, and even if you don’t want to call it “intralingual translation,” as an exercise it uses the translator’s toolkit. A thesaurus is like a bilingual dictionary for a single language. The work of art is said to be universal, inimitable, and timeless. Paradoxically, translation puts the lie to these three things, all while enabling them.

If a translation proves timeless, it’s a happy accident of reception that owes the most to readers, and their belief (from any number of factors) that the language of a certain period is still appropriate to a particular work. If people still stand by the Constance Garnett [one of the first English translators of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, and credited with introducing them widely to Anglophone audiences] renderings of major Russian authors despite liberties and errors later critics are all too eager to point out, it’s because somehow it jibes with some widely shared, culturally determined conception of how this literature should sound, and not because her translations most closely approach some absolute standard of accuracy, fidelity, or truth of spirit, though this is the language most likely used by supporters and detractors alike, which is why I feel translation’s basic position needs reframing.

I used to overpolice my English for standard usage and some notion of normalcy, because even as a fledgling translator I knew any deviations therefrom would be blamed on me (and not the author), and I was afraid of that. That’s relaxed into a somewhat philosophical but mostly ironic detachment at the game of changing and sometimes arbitrary fashions language really is. These days, I think more along the lines of “whose English?” it is, exactly, that I am working into, and why I’ve adopted it. I also have this pet thought experiment of extrapolating along likely lines of language evolution with a linguist and translating something into the English of a decade from now.

I feel translated titles in general don’t get the exposure they deserve in the publishing world, which makes me ever grateful to emissaries like you to expand/enhance my reading. Any thoughts on encouraging more reader consumption/demand?

Advocating for translations is not quite the same as advocating for translators. A publisher can pour a lot into backing a foreign book while downplaying the fact that it is translated. At the same time, in addition to their central underpaid role, translators are expected to play many others for free: bilingual go-between, author spokesperson, sometimes even agent and rights person. The first hurdle translators need to clear is giving people a clearer idea of what their work entails, and in so doing, reframe the expectations surrounding translation. I can’t help but feel that greater comfort with the fact of translatedness will lead to greater embrace of translated literature, and the first thing people need to be disabused of is that translation somehow produces an equivalent or a reproduction. I think people actually know this and will admit it when pressed, but otherwise default to the more conventional notion. And I think a lot of the outsized, incommensurate rage you see in people when attacking perceived mistakes in translation derives from not liking being reminded of a fact they know perfectly well but repressed or refused to acknowledge. They feel they were promised a glass pane, and get mad when it’s not one, even though they know no translation can be a glass pane.

I don’t know that I have any global strategies to encourage reader consumption; it’s easier for me to think in niches. I think one salutary development I’ve seen in the last 10 years of French comics in America is that there’s now such a variety of comics being brought over, nothing really unites them as French anymore. They’re free to be their own thing, join domestic canons, conversations, and genres; they’re not beholden to some restrictive notion of France. Whereas when there were fewer French comics coming over, the burden was incumbent upon them to somehow represent some element of Frenchness, a national reputation we had constructed on these shores, which in turn informed the kinds of French comics editors would look for.

In addition to translating, you’re also an author, and working on a fiction writing graduate degree. Has translating affected your own writing process?

I’m due to finish my degree soon, and in the meantime, am seeking representation for a collection of short stories, half of which have appeared in literary magazines over the last decade.

My answer to the second was a knee-jerk no, not in any way. There was no mutual influence. I was a writer before I became a translator, and much of what I translated for a living in no way coincided with my personal interests. I’d even lie in response to this question, just to make its askers feel like they’d gotten something like the answer they were looking for, and claim French syntax had helped me handle long, elaborate sentences in English. When in fact it was probably the other way around: an ease and fascination with long sentences predisposed me toward liking them in French.

I still think the spheres are largely separate. If anything, I seek out authors who are nothing like me, who write what I could not ever imagine myself writing – that’s where all the fun lies in pretending to be them! Translating someone too much like myself would probably make me feel jealous. But I wonder if I haven’t become a better mimic through translation – for instance, in this story of mine at the Saturday Evening Post [“Raymond Chandler”] – since that’s not something I used to think of myself as good at.

A certain “work amnesia” other writers and translators have talked about affects the products of both: you get it out and forget it, though it actually remains a part of you, later surfacing in unexpected ways only a third party can more clearly point out.

I also think translation, like any other profession a writer has, tempts readers with a “handle” that is useful for marketing but not necessarily applicable to their work. Bits of biography cloud our readings of things because, thus informed, we go looking for evidence of them, and often as not find them as a result of determined looking. Which is to say, French will always be a valid way of reading my English, but not necessarily the most pertinent.

When you become that major published author yourself and translation rights sell worldwide, what are your hopes/requests for your international translators-to-be?

Anne-Sylvie Homassel is a dear friend who’s translated three of my stories to date, publishing them in France in the fantastical revue Le Visage Vert and the digital science-fiction magazine Angle Mort. Another appeared in Brêves, translated by Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud, the first author I ever translated. I’d like to take a long road trip with all of them in a converted school bus, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert-style.

Published: “Talking with: Edward Gauvin,” The Booklist Reader, July 29, 2019