15 Oct / Requiem by Frances Itani

While I can hardly estimate the many, many books I’ve read about the Japanese American experience during World War II, I know few details about what happened to Japanese Canadians. The lone fact that looms is that like their Japanese American counterparts on the West Coast, more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians along Canada’s west coast were also rounded up and imprisoned without cause to harsh camps. The one title I’ve read that puts a face to the unjust experiences of our northern neighbors is the modern classic, Obasan (and its middle grade version, Naomi’s Road) by Joy Kogawa. Until now …

While I can hardly estimate the many, many books I’ve read about the Japanese American experience during World War II, I know few details about what happened to Japanese Canadians. The lone fact that looms is that like their Japanese American counterparts on the West Coast, more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians along Canada’s west coast were also rounded up and imprisoned without cause to harsh camps. The one title I’ve read that puts a face to the unjust experiences of our northern neighbors is the modern classic, Obasan (and its middle grade version, Naomi’s Road) by Joy Kogawa. Until now …

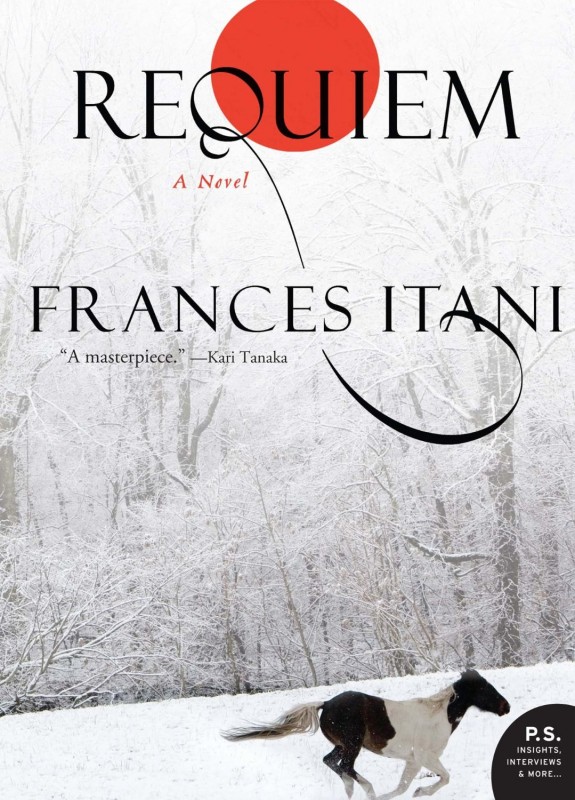

Intentional or not, Frances Itani – whose best-known title, Deafening, won the 2004 Commonwealth Book Prize for Best Book (Caribbean and Canada) among numerous other honors – seems to be channeling Kogawa in her Requiem. In my own reading (alternating with Brian Nishii’s excellent narration stuck in my ears when the book was not in hand), Auntie Aya’s appearance in Itani’s latest provided the initial trigger: the eponymous Obasan in Kogawa’s autobiographical novel is also an Aunt Aya, whose full name is Ayako Nakane. Both titles also share a counterpoint structure, shifting between the defining events of World War II and a contemporary examination of things past.

At the risk of committing literary heresy, Requiem is the better novel. I pause for a moment in anticipation of the roaring objections to come …

Bin Okuma – who throughout his life has also answered to Oda Binosuke, Okuma Binosuke, Bin Oda, Ben Okuma – is newly widowed, his beloved wife having suddenly died of a stroke at just 49. Lena was the historian, the one who pieced together Bin’s family story, even as he tried to bury his anger, his melancholy, his unresolved mourning. Loading the car with the family dog Basil – quite the character in his own right – Bin literally journeys into his past, driving through his Canadian homeland, seeking the remote prison camp where he spent four years of his childhood, where his family was splintered and remade, where he might finally confront the man he calls “First Father.”

So aptly titled, Itani creates a resonating symphony of intertwined lives – separating, flowing, diverging, merging. Even as she captures moments of inexplicable violence (a father scarring his son with a careless toss), of systematic betrayal (reducing a man’s worth to just $18.85 for nothing more than the randomness of his ancestry), of shocking tragedy (a family giving away an extra son), Itani always remains in subtle control, modulating each detail with careful mastery.

Dare I say … the result warrants a (tear-stained, breath-taking) ovation.

Readers: Adult

Published: 2011 (Canada), 2012 (United States)