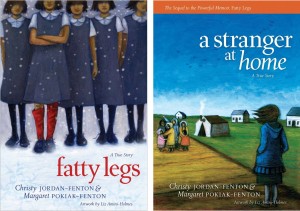

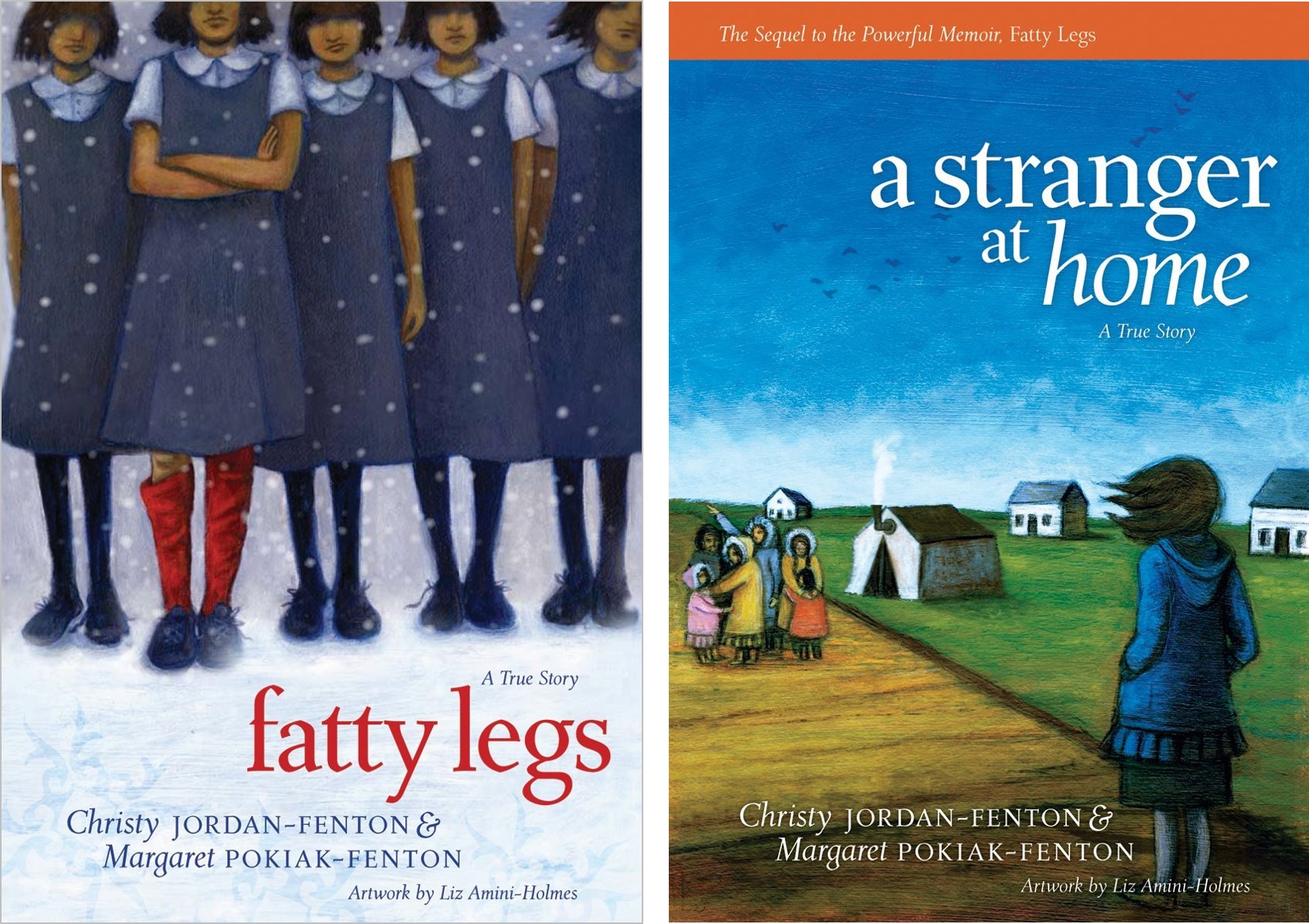

07 Mar / Fatty Legs and A Stranger at Home by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, illustrated by Liz Amini-Holmes

Reading these double memoirs of a native Inuit girlhood during the 1940s in far northern Canada is a searing experience. What was done to children disguised as progress and opportunity (not to mention in the name of a Christian God) is a tragedy that is taking generations to reconcile, a healing process that continues today. And yet in spite of the suffering, both titles are a celebration of resilience and strength.

At age 7, Olemaun – pronounced OO-lee-mawn – Pokiak becomes entranced with the idea of reading. Her older half-sister Rosie has spent four years at the “outsiders’ school,” which has given her the remarkable ability to render amazing stories from a printed page. Olemaun, too, wants to read, and begs her father to let her go to school. But because he’s experienced the outsiders’ world himself, including surviving their school, he’s remained adamant about keeping his younger children safe at home on their remote Bank Island home in the Arctic Ocean. Olemaun’s family is Inuvialuit, and adheres to their traditional ways which “allowed them to cope with the natural environments they lived in.”

In Fatty Legs, Olemaun finally gets her wish. Her excitement over learning to read is utterly overshadowed by the ordeal she must survive: her Inuit name is replaced with Margaret, her native language forbidden, her hair shorn, her clothing taken away and replaced with a scratchy uniform inappropriate to the harsh climate, her usual diet replaced by food she can hardly digest. Her little 8-year-old body will be worked daily with unrelenting chores demanded by the nuns – especially the hooked-nose, abusive Raven. For two years, Margaret endures her outsiders’ so-called education, buoyed by a few books, her best friend Agnes, and a single kind nun, until she is reunited with her family.

By the time she is finally standing in front of her parents and siblings, however, Margaret is 10, and so changed that her mother initially doesn’t recognize her. When she finally hears her father call her name for the first time in two years, “[t]he Inuit name my grandfather had given me felt strange to my tongue … I no longer felt worthy of it. It was like a beautiful dress that was far too big for me to wear. At the school I was known only as Margaret. Margaret was like a tight, scratchy dress, too small, like my school uniform. Not wanting my father to see that I was no longer his Olemaun, I buried my head against his chest.” A Stranger at Home details Margaret’s difficult, aching journey to reclaim her language, her culture, her relationships, and her very identity as Olemaun.

Written by Olemaun Margaret together with her daughter-in-law Christy, and deeply enhanced with both rich original artwork by Liz Amini-Holmes and haunting black-and-white period photographs, this two-part memoir bears witness to the remarkable fortitude of some of the youngest victims of colonialism: “As Europeans spread throughout North America, their quest to expand into new territories led them to seek ways to remove the people who already inhabited the land,” explain the authors in a final historical chapter. “One way to do this was to send Aboriginal children to church-run schools where their traditional skills were replaced by those that would equip them to function in menial jobs.” Some Inuit parents saw the schools as the only way to prepare their children “for the rapidly changing world” and sent them voluntarily. Other children were actually kidnapped. These overcrowded, disease-ridden schools – too often run by unqualified teachers – were as much about producing free labor as they were actual places of real education.

For Olemaun Margaret – and so many like her – sharing her story proves to be an act of healing. To read, listen, and learn can, in some small way, be our act of acknowledging and encouraging other survivors to hopefully do the same.

Readers: Middle Grade

Published: 2010 and 2011