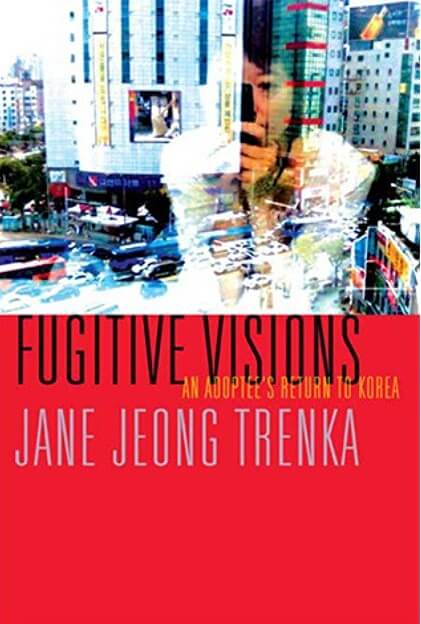

25 Jul / Fugitive Visions: An Adoptee’s Return to Korea by Jane Jeong Trenka

Jane Jeong Trenka‘s follow-up to her phenomenal debut memoir, The Language of Blood, is a searing, disturbing account of why transracial adoption does not work. Newly divorced, having severed her relationship with her adoptive parents, escaping from a violent stalker now in jail, Trenka arrives in Korea having sold or given away most of the reminders of her American life.

Jane Jeong Trenka‘s follow-up to her phenomenal debut memoir, The Language of Blood, is a searing, disturbing account of why transracial adoption does not work. Newly divorced, having severed her relationship with her adoptive parents, escaping from a violent stalker now in jail, Trenka arrives in Korea having sold or given away most of the reminders of her American life.

Instead of being the mother and wife that she “had always imagined [her]self … the only options for women raised in rural Minnesota,” she lives alone “in Seoul like a student, or a monk, in a room measuring five meters one way and five the other.” The one reminder Trenka firmly retains is the music she played with such tenacious devotion, although the instrument itself is long gone … so vivid are those notes that her book is an anguished literary expression of Sergei Prokofiev’s Visions Fugitives, the 20 parts of which she mimics through the eight chapters of this heart-wrenching title.

Trenka’s life is defined by dissonance. In Minnesota, she was never without cruel reminders of her foreign birth. When she emigrates back, she finds she has arrived too late to speak the Korean language without an accent, without paralyzing difficulty. She cannot go anywhere without intrusive interrogations as to who – or what – she really is. Her very being, on either side of the world, is under constant threat.

“When I came to Korea to live, I could measure exactly how much had been not lost – but methodically destroyed,” Trenka writes with such raw, unblinking honesty, you will not be able to close the pages, to turn away.

“The destruction of the identities and histories of the adoptees wasn’t at all personal. It was just methodical … Our Korean mothers … didn’t know that adoption would erase the people who we once were so completely, so irrevocably. Our adoptions would take our language, our culture, our families, our names, our birth dates, our citizenship, and our identities in a perfectly legal process. And the world would view it as charitable and ethical.”

Some 200 Korean adoptees have returned to Korea to live, seeking – and finding – their birthfamilies. In spite of the reunions – or because of – too many remain untethered and lost, much as Trenka’s return to her birthfamily continues to fuel her loneliness: “My longing has always been exactly the same: I want love. I want to be safe. I want to go home.” True comfort remain elusive: “How these simple wishes have gone unfulfilled, how warped they have become as I have traveled through life seeking love, safety, and home from strangers, just as the moment I arrived an alien and daughter into the home of my American parents.”

After finishing Mei-Ling Hopgood’s vastly contrasting transracial adoption memoir, Lucky Girl, reading Visions is a jolting shock, filled with questions about how families get made, how they stay together. Somehow, Hopgood found love, safety, and home … Trenka remains adrift, yet determined: somewhere, in the spirit of uri, of we, “Let me believe in the humanity of other people. Let them believe in mine.”

Readers: Adult

Published: 2009