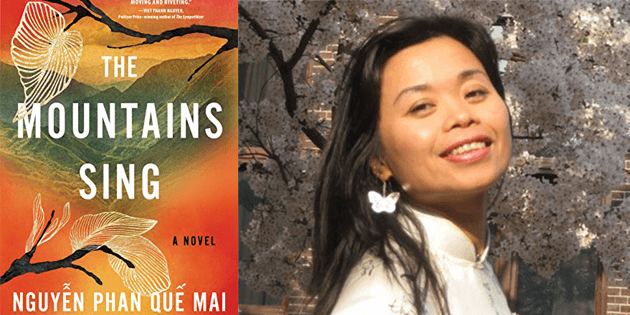

01 Apr / The Mountains Sing by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai + Author Interview [in The Booklist Reader]

Filling a Lack of Voices from Inside Việt Nam: Talking with Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

Filling a Lack of Voices from Inside Việt Nam: Talking with Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

Thousands of Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s devoted readers should have been meeting her live over these next few weeks to hear about The Mountains Sing, her first novel in English. But an unprecedented pandemic has made the Indonesia-based Nguyễn’s worldwide tour impossible for now. What you can do, of course, is read her book (for those without access to a physical copy, it’s available virtually from your local library, to download either as an e-book or even an audiobook). While the book’s only been out since March 17, the praise has been endless, flowing from most-anticipated and book-of-the-month lists to glowing reviews and endorsements from fellow literati.

“If our stories survive, we will not die, even when our bodies are no longer here on this earth,” one of Nguyễn’s characters insists. What emerges in Nguyễn’s expansive fiction is the ominous history of twentieth-century Việt Nam told through four generations of a single family. As a privileged 1930s teenager, Diệu Lan has a bright future overshadowed by a fortune teller’s prescient warning of “a very hard life.” The tragedies begin with her father’s gruesome murder by invading Japanese; her mother, husband, and brother also suffer separate, brutal deaths. Diệu Lan miraculously survives the mid-1940s famine of the Great Hunger and the savage 1950s Land Reform to raise her six children. Fast forward to the 1970s, when Diệu Lan is again doing everything possible to keep a loved one alive, this time her only granddaughter, Hương, whose parents and uncles are missing at war. Some will return, almost unrecognizably damaged, to continuing conflicts even at home.

Already widely published in Vietnamese, poet/nonfiction writer/translator Nguyễn balances the unrelenting devastation of war with redemptive moments of surprising humanity.

You’ve written 11 books of fiction, poetry, and nonfiction in Vietnamese and English. The Mountains Sing is your debut novel and first fiction book in English. How and when did you decide you were ready to write in English?

I think my creative adventures into the English language began when I started working as a translator around the year 2008. I found myself enjoying transferring Vietnamese elements of my culture into the English language. I translated because I saw the need for international readers to know more about Việt Nam; that’s why I introduced Vietnamese poetry on Prairie Schooner and coproduced “Lanterns Hanging on the Wind” for a radio program. But I think the need to write The Mountains Sing started burning fiercely when I realized I needed to respond, with my art, to Hollywood movies and novels written by those Westerners who continue to see Việt Nam only as a place of war and our people as individuals who don’t need to speak – or, when we do, we sound simple, naïve, cruel, or opportunistic. The canon of Việt Nam war and postwar literature in English is vast, but there is a lack of voices from inside Việt Nam.

Where did you find the amazing story for this book? I can’t remember any titles in English that include the mid-1940s Great Hunger and the savage 1950s Land Reform – those narrative elements alone make this novel stand out. What made you decide to weave in that history?

While The Mountains Sing is a work of fiction, it is dedicated to my paternal grandmother who perished in the Great Hunger together with her youngest son and her brother. I had already written a poem about her. The novel is also inspired by my maternal grandfather who died because of the Land Reform, and whose face I sketched in this poem. When I researched the Great Hunger and the Land Reform, I found little written about either in fiction. The histories of those events, as well as many other historical events of Việt Nam, are held in the memories of the elder generation and I was afraid if I didn’t document them, they would be lost someday.

It was my intention to write a large story that encompasses these many historical events but I didn’t find a door into such a story until one day when I was traveling in a car with a Vietnamese friend. I asked him where he was during the war. He told me when he was 12-years-old, living in Hà Nội with his grandma (his parents were in Russia at that time), American bombers attacked the city. His bombing experiences were so horrific that more than 10 years after, he could not travel on an airplane. His story moved me so much that I had to write about it. That night, after having cooked my children dinner and put them to bed, I sat down at my writing desk. It was late and I googled about the bombings of Hà Nội in 1972. With tears running down my face, I wrote the 2,000 words that would become the first scene of The Mountains Sing.

In this first scene, my friend’s grandma became Grandma Diệu Lan – the grandmother I always wanted because both of my grandmas had died before I was born. I became little Guava (Hương) who got to listen to her family’s history via her grandma. I did not know where the story would go, but I knew I wanted the characters to have a large family, each member bearing witness to a part of Vietnam’s complicated history. Over the seven years of writing and editing the novel, I made many significant changes. I restructured the novel many, many times to create different arcs. It was very challenging but I never felt like giving up. I was writing it as part of my masters in creative writing program so my mentor Sara Maitland and my fellow students cheered me on. My ancestors were with me the whole way. And they are still with me, smiling down on the book.

And this friend – have you been able to give him a finished copy? What were his reactions?

I’m in regular contact with my friend who is in Hà Nội at the moment. I sent him a draft of the manuscript when it was quite rough; he read it and told me he liked it a lot. I have his name in the acknowledgement section. I have just received the final copy of the book and I am signing it and sending it to him. Apart from that first scene of the novel, my friend’s experiences are not reflected in the novel. The Mountains Sing fictionalizes the experiences of many people whom I talked to during my life time. For example, the story of Grandma Diệu Lan is inspired by my wish to have a grandmother but also by the experiences of my friend’s grandmother: she was born into a rich family and fell victim to the Land Reform.

Speaking of translation, you’ve rendered seven books from English to Vietnamese, and Vietnamese to English. I noticed – and so appreciated – all the diacritical usage in The Mountains Sing: Việt Nam vs. Vietnam, for example. That accuracy felt like both reclamation of language and rejection of colonial elision. Did you have to deal with any pushback from your editors?

I have been doing my PhD and one of my research questions is how to maintain the Vietnameseness of my writing in English. The Vietnamese language has suffered a lot of losses due to colonization. Our language, when published outside of Việt Nam, is often stripped of diacritical marks to fit the Western eyes and ears. I discussed with my editor that if we published Vietnamese language without the marks, we would be misspelling the words. Those marks might look strange at first, but they are as important as the roof of a home. The word “ma,” for example, can be written as ma, má, mà, mả, mạ, mã, each meaning very different things: ghost, mother, but, grave, young rice plant, horse. The word “bo” can become bó, bỏ, bọ, bơ, bở, bờ, bô, bố, bồ, bổ: bunch, abandon, insect, butter, mushy, shore, chamberpot, father, mistress, nutritious.

My editor Betsy Gleick is so amazing and agreed to publish the Vietnamese in its entirety. I use a lot of Vietnamese in the book, including Vietnamese names. It is a bit of a risk to do so because a reader could say: this is too complicated with all the names in tonal marks, I can’t read it/I don’t want to read it. So I really appreciate Algonquin supporting my decision. The copyeditor, though, wanted to change Hà Nội, Sài Gòn, and Việt Nam to the typical English spellings and I had to convince him that I wanted to preserve the authentic Vietnamese setting of my novel.

I would like to thank readers of the book who accept the challenge of fully immersing themselves in Vietnamese culture by reading The Mountains Sing. It is not just diarictical marks, but you might have noticed that I do not always translate Vietnamese words. For example, early in the book, the reader learns that nón lá is a conical hat made of woven bamboo and palm leaves, and then I continue to use nón lá without repeated explanation. It’s my intention to familiarize the reader with the Vietnamese culture as much as possible, so that hopefully by the end of the novel, they become a part of it.

I find I have this struggle often when filing certain reviews, especially in terms of Asian names. Even book publishers often don’t understand how important the diacriticals are! Kenzaburō Ōe without those long ōs is like writing Barack Obama as Bara Oba . . . and yet the marks still get lost!

I know. I am so impressed, though, that many American presses are printing reviews of my book with the diacritical marks. I must tell you that when I received the final copies of the book, I cried looking at my name the way it appears in Vietnamese: Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai. These little marks define us. A part of my name, Quế, for example, means cinnamon; without the marks, it’s Que (a stick).

And as your writing progressed, how did your linguistic agility affect your composing/editing/finishing in English?

I wrote this novel in English but with the mindset of a Vietnamese who is fully aware of the need to preserve the Vietnamese authenticity of her novel. My Vietnamese characters think and speak in Vietnamese, yet I have to transfer their thoughts and speech into English. My responsibility as a translator is to capture the Vietnamese essence of such expressions and not Westernize them.

Proverbs and idioms play a crucial role in the daily conversations of Vietnamese people and I came to realize that their frequent use should be reflected in The Moutains Sing. Doing so reveals Vietnamese traditions, ways of thinking, and social customs. Idioms and proverbs, however, can be problematic. In English language literature, using proverbs is traditionally considered cliché. Therefore, I was selective in the use of proverbs, which are unique to Vietnamese culture. For example, this proverb, “mưa dầm thấm lâu” – soft and persistent rain penetrates the earth better than a storm – is about the value of patience. It is unique because Việt Nam is a tropical country so it rains a lot and the phrase would be natural for Grandma Diệu Lan to use because she is a farmer and works with the earth.

You’re quite the literary chameleon: novelist, poet, translator, editor, essayist, journalist, creative writing teacher, and soon to be PhD-ed. How do you balance all those identities?

All of those identities help make me into the person I am today. I couldn’t have written The Mountains Sing without being a translator, poet, essayist, journalist, creative writing teacher, as well as a PhD researcher. Different aspects of all this work have found their way into my debut novel. I like to do many things at the same time as they keep me away from experiencing writer’s block. They also help me to learn. For example, I have been teaching a group of Afghan refugees how to write creatively and because their English is quite basic, I encourage them to write in their native tongue. Our working process has inspired me to inquire further into my Vietnamese language and culture and how to infuse that language and culture into English. Việt Thanh Nguyễn once said, “Writers from the majority can assume their audiences know what they’re talking about – they don’t have to explain things, whereas minority writers are expected to,” and that it’s time for us minority writers to make changes. As a result, The Mountains Sing challenges readers to engage fully with the Vietnamese culture.

If you were to devise a reading list for Anglophone readers with limited knowledge about Vietnam, what would be a few texts you might suggest and why?

Anglophone readers, if they read fiction from Việt Nam, will often reach for Bảo Ninh’s The Sorrow of War or Dương Thu Hương’s Paradise of the Blind. While these books are among my favorites, they were written quite a while ago. For a more contemporary look at Vietnamese fiction, I can recommend Trần Thị Trường’s Phố Hoài, Tạ Duy Anh’s Mối Chúa, Nguyễn Quang Lập’s Kiến, Chuột và Ruồi . . . however these books have not been translated into English. My novel, of course, provides a comprehensive picture of Việt Nam and is readily available. In the future, I would like to push translation projects that introduce more work from Việt Nam. We currently have little funding for such projects. My years of translation have been an act of donation. There is so much international readers should know about my homeland that can be understood via our literature.

When it comes to fiction from diasporic Vietnamese writers, Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is a must read, as well as Kim Thúy’s novels. Việt Thanh Nguyễn’s sequel to The Sympathizer (The Committed) will be published soon and I am most excited about it. I love Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do, Thanhhà Lai’s Butterfly Yellow . . . There are so many good books by diasporic Vietnamese writers that my list goes on and on. But because the works of diasporic Vietnamese writers in English is easily accessible, I would like to promote literature from within Việt Nam first and foremost because we don’t have an equal chance. For many, many years, there has not been a book from inside Việt Nam which has gained international recognition. Believe me, the stories from inside Việt Nam are good, they simply have not yet been translated and promoted properly.

After being born in Việt Nam, studying in Australia and the UK, returning to Việt Nam to work, how did you end up currently living in Indonesia?

After my study in Australia, I had an opportunity to stay there and work, but I turned it down. I wanted to return to my homeland and make a contribution (I was on a scholarship and felt the need to give back). Within a few months of returning home, I met my husband, who is German. The day I met him was the happiest day of my life, but I also felt devastated because I knew he would be traveling around the world for his job. After five years together in Việt Nam, we moved to Bangladesh, then back to Việt Nam, then to the Philippines, Belgium, and now Indonesia. But there’s a Vietnamese idiom: Trong cái rủi có cái may (Good luck hides inside bad luck). Because of our frequent moves, I had to establish a career that I could bring along with me. So I started writing seriously. I applied for a scholarship at Lancaster University (distance learning) in the UK and started writing The Mountains Sing in Manila, Philippines, as part of my master’s thesis. I got another scholarship for my PhD from Lancaster, which allowed me to write a second English novel. I keep in touch with Việt Nam by writing regularly in Vietnamese for different journals and newspapers about social, literary, and cultural issues. I am also active in charitable work: I manage two scholarship programs from afar. These days, you can do so much with the help of the Internet. All you need is the will to do it and the willingness to share what you have.

Whooo hooo! A second novel! Can you tell us eager readers a bit about it?

In Vietnamese culture, we believe “nói trước bước không qua” (“if announced, one can’t step over the hurdle”). So please let me keep the story of this novel to myself until I sign a publishing deal. What I can reveal is that I have finished drafting it and am currently polishing the final edits before showing it to my agent. The novel is inspired by my childhood experiences and I am taking further adventures into the English language by writing in the voice of an American man as well as Vietnamese characters.

Alas, your extensive U.S. tour is on hold for now . . . but surely, it’s going to happen! And WHEN you embark, what are you looking forward to most?

I am devastated by the current situation and hope we can work together to defeat this coronavirus pandemic soon. I hope that everyone stays safe and healthy and my heart goes out to those who have been affected. I am thankful to medical professionals who are saving lives while risking their own, and to those who are working hard to keep our economy going so that food is still being produced and books being distributed to readers.

I hope the book tour can still happen in the near future so that I can meet and thank my readers for the incredible support they have shown me. During the past weeks, I have received many heartfelt messages from people all over the world. I also look forward to giving support to independent booksellers during my tour. They are being hit very hard by this pandemic and have been doing such an incredible job in delivering books to readers. They are my heroes!

What’s the one message you want your readers to remember after reading your book?

I hope that while reading The Mountains Sing, the reader will join me in embracing the values of peace, normality, and family. As in the words of Hương: “I had a wish, I would want nothing fancy, just a normal day when all of us could be together as a family; a day where we could just cook, eat, talk, and laugh. I wondered how many people around the world were having such a normal day and didn’t know how special and sacred it was.”

Author interview: “Filling a Lack of Voices from Inside Việt Nam: Talking with Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai,” The Booklist Reader, April 1, 2020

Readers: Adult

Published: 2020

Author photo credit: Vũ Thị Vân Anh